The Aran Sweater - From Tragedy to Timeless Irish Icon

Synopsis

-

The Aran sweater originated in the early 1900s, not in ancient Irish antiquity.

-

It was created as a functional working garment for fishermen, using thick, lanolin-rich undyed wool.

-

Its development was supported by the Congested Districts Board, which promoted knitting as a cottage industry to relieve poverty.

-

Cable patterns were chosen for structure, insulation, and durability, not for symbolic or mystical reasons.

-

There is no historical evidence that Aran patterns represented families, clans, or were used to identify drowned sailors.

-

Myths surrounding Aran sweaters largely stem from literature, tourism, and modern marketing, not tradition.

-

Invented heritage narratives can mislead consumers, while new traditions are valid when openly acknowledged.

-

The true cultural value of the Aran sweater lies in the history of hardship, innovation, and survival of the Aran Islanders.

Aran sweaters are a staple of traditional Irish dress and have become wildly popular around the world thanks to their unique combination of beauty and practicality.

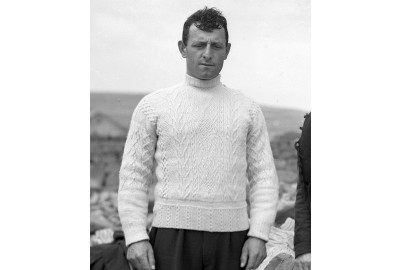

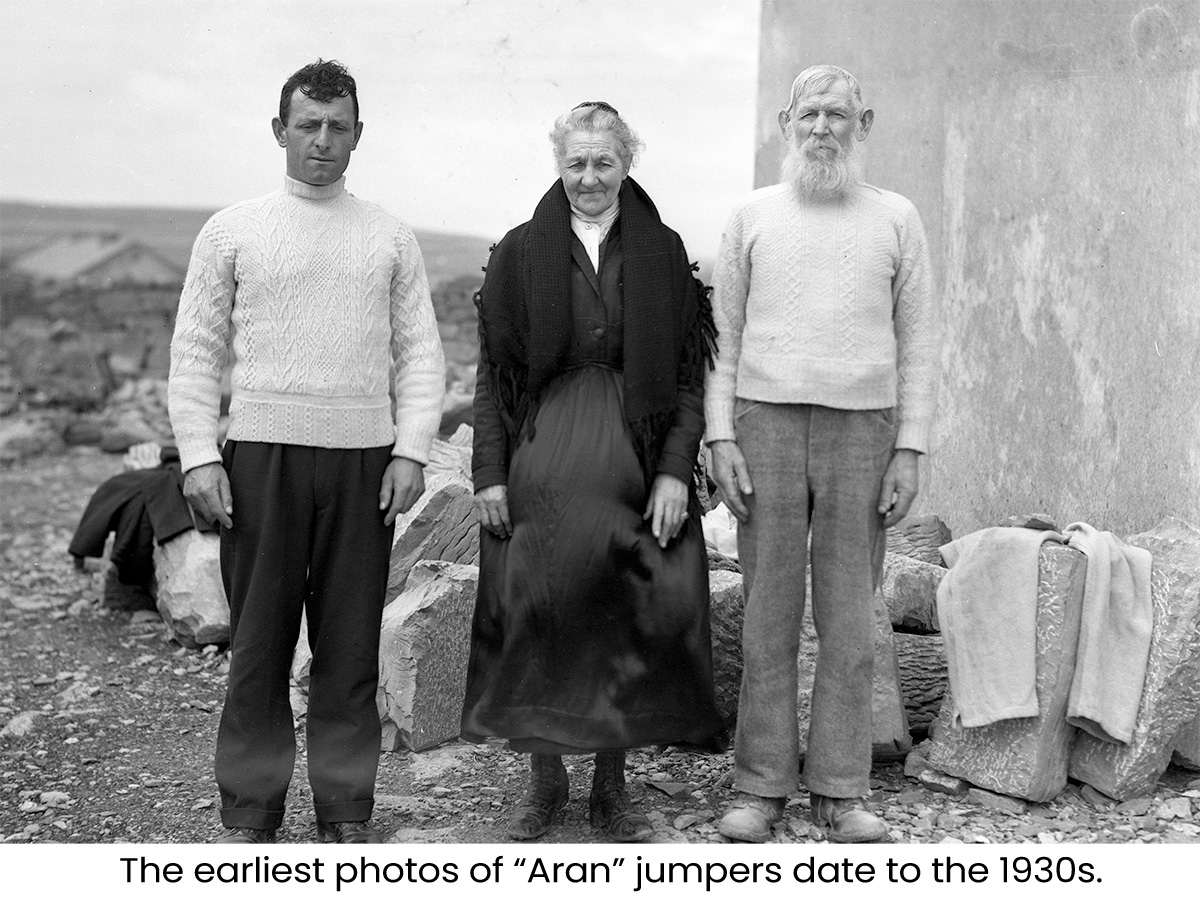

The Aran jumper (Irish: Geansaí Árann, aka "guernsey", "pullover", "jersey", "sweater") is a working man's garment that takes its name from the Aran Islands off the west coast of Ireland. A traditional Aran Jumper is usually cream or charcoal because it is knitted from undyed báinín (pronounced "bawneen"). This unscoured wool retains its natural oils (lanolin) making this fisherman’s sweater naturally water-repellent; wearable and warm even when wet.

The most distinctive feature is, of course, the cable patterns on the body and sleeves. Most today feature 4–6 cabling patterns, each about 2–4" in width, that move down the jumper in symmetrical columns.

From the 1930s onwards, the Aran sweater gained a steadily growing popularity across Ireland, then the UK and the United States and Canada. This was spurred mid-century by adventurous outdoorsmen and then media figures including Steve McQueen, Elvis Presley, Grace Kelly and Marilyn Monroe - all of whom appeared in film or photoshoots wearing the garment. Much more recently you will see stars like Chris Evans, Taylor Swift and Adam Driver wearing it.

The Aran sweater has always straddled class since it is at once a truly authentic workingman's garment and also just plain beautiful (not to mention cozy). Anyone can wear one and look great. And for most Americans it is synonymous with “Ireland.”

But now it’s time to look at the stitches of this iconic item. There is as much myth surrounding it as there is history. Warning: Sad facts and debunking ahead.

Where did the Aran Sweater come from?

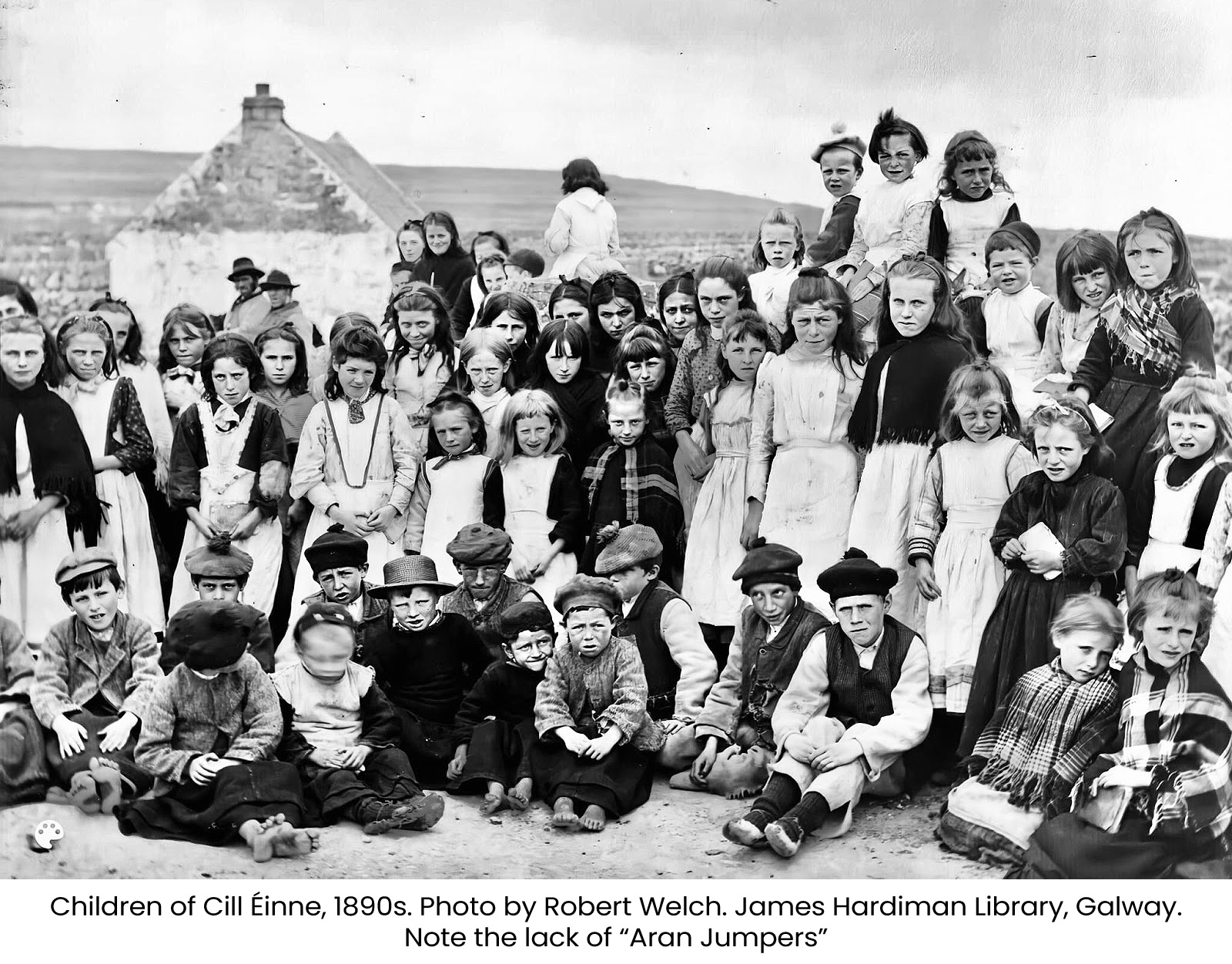

Most historians agree that Aran knitting developed as recently as the 1890s or early 1900s. It is not ancient. In fact the Aran sweater was more or less intentionally invented. Not a native form of folk dress, but rather a tool created to help relieve a crisis.

Beauty That Grew Out of Irish Suffering

Throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th, the people of the Aran Isles were among the poorest and most vulnerable in Ireland, regularly succumbing to famine and disease due to their abysmal living conditions.

How poor were the Aran islanders?

Farming on the isles had always been on a subsistence level. Nothing more ambitious was possible due to the rocky terrain and extremely poor soil. To create potato fields, people had to transport, by hand, sandy mud from the beaches up to their farm plots. Here the dirt would be spread to a thickness of about six to twelve inches. Lack of rain could mean utter disaster as the soil on top of the rock would not retain any moisture. In many years, no rain meant no crop; ironically the opposite of the rest of Ireland where heavy rain could lead to blight. Famine being the outcome in either case.

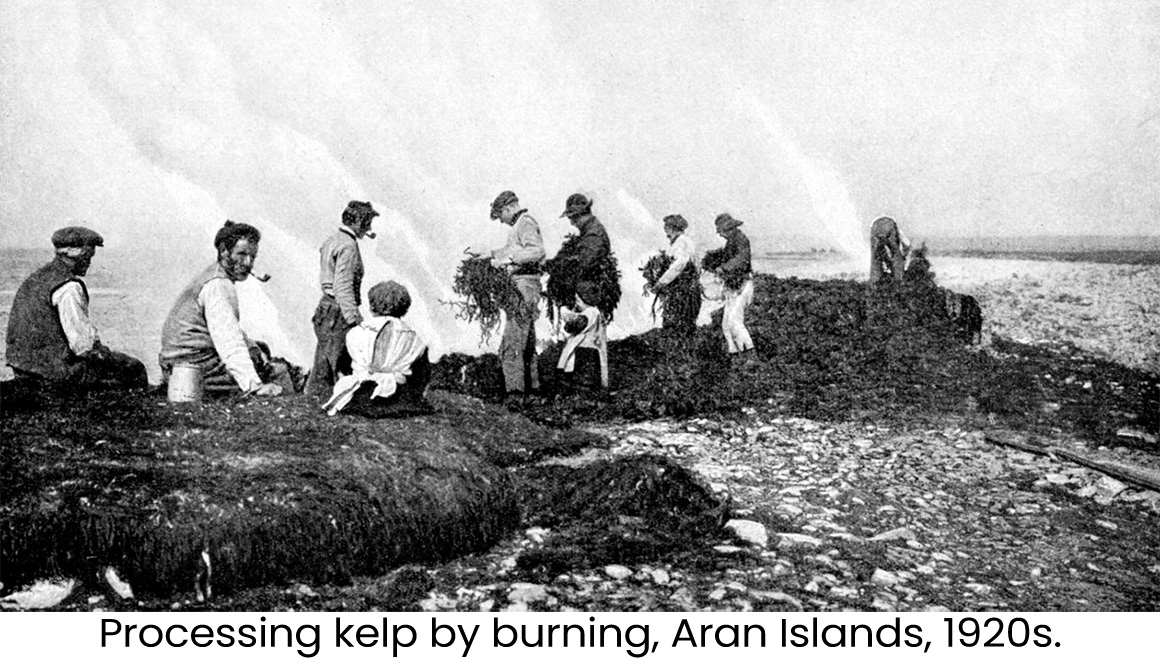

Aran families supplemented their income by collecting kelp from the shore which was then transported to the mainland and sold to factories that extracted iodine from it. This was dangerous, backbreaking work that yielded little profit (at best around £4 per ton), even when demand was high. And yet it was essential because it was the primary source of cash to pay rent to landlords.

And then there was fishing. Though considered an “industry” this was in fact mainly subsistence, like the potato fields.

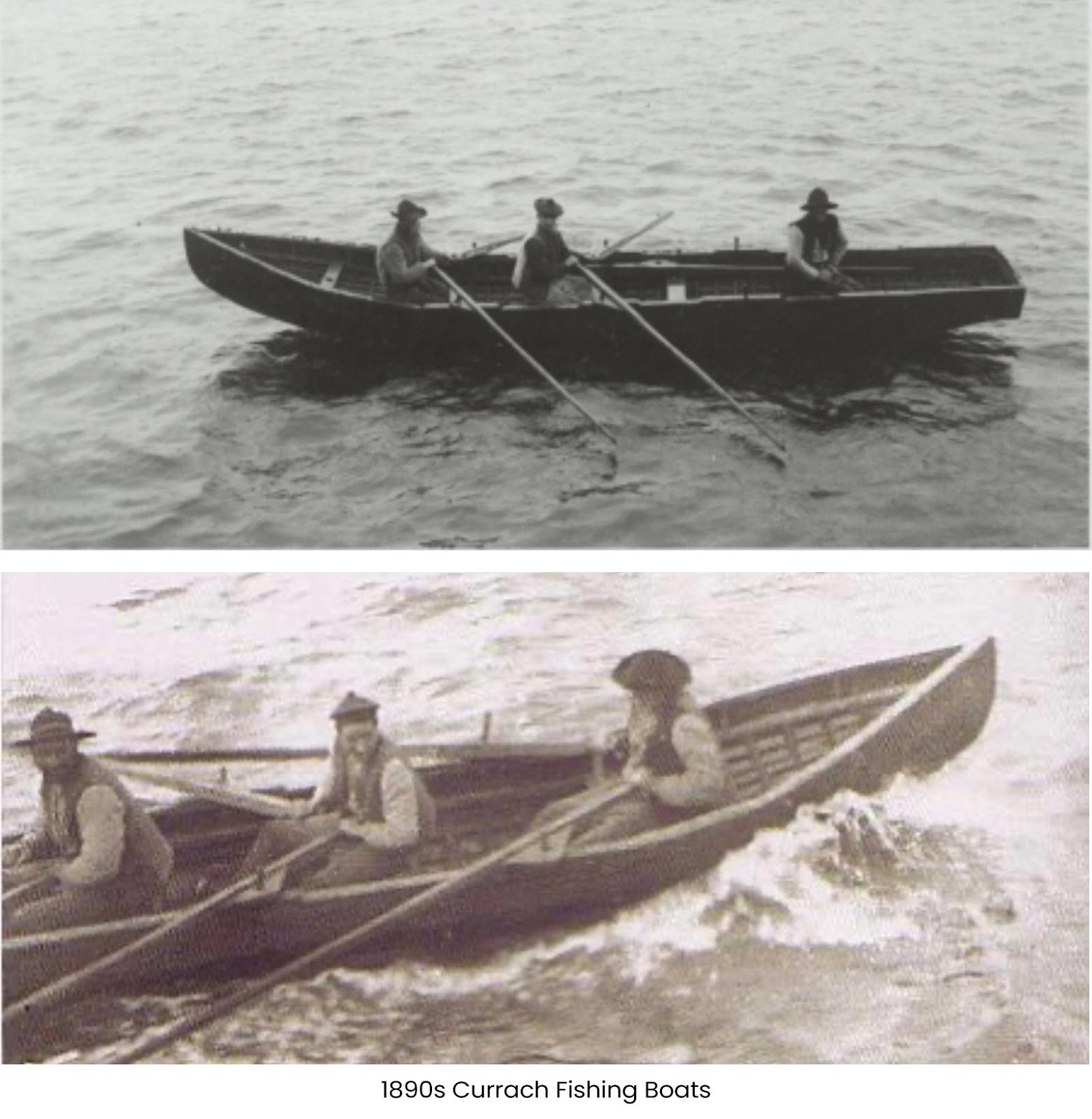

Fishing was a constant struggle against the merciless Atlantic using primitive technology. Unable to afford or maintain better equipment, fishermen relied on currachs. These lightweight canoe-like boats consisted of a wooden frame covered in tarred canvas or animal hide. Usually they carried five crewmen. Fishing consisted of stretching nets between several boats in a fleet to form a catch line. Mackerel was the main catch.

While relatively nimble, the currachs were vulnerable to sudden winds and punctures. Their primitive design meant fishermen could not venture out in bad weather and were often stranded on shore for weeks. However, need typically drove the Islanders to take horrendous risks.

Drownings were common, with entire communities experiencing loss. One report from around the turn of the 20th century recorded that over twenty women in the village of Cill Éinne had lost their husbands to the sea.

On top of this, fishermen were sometimes banned by their landlords from fishing at all.

Enter the CDB.

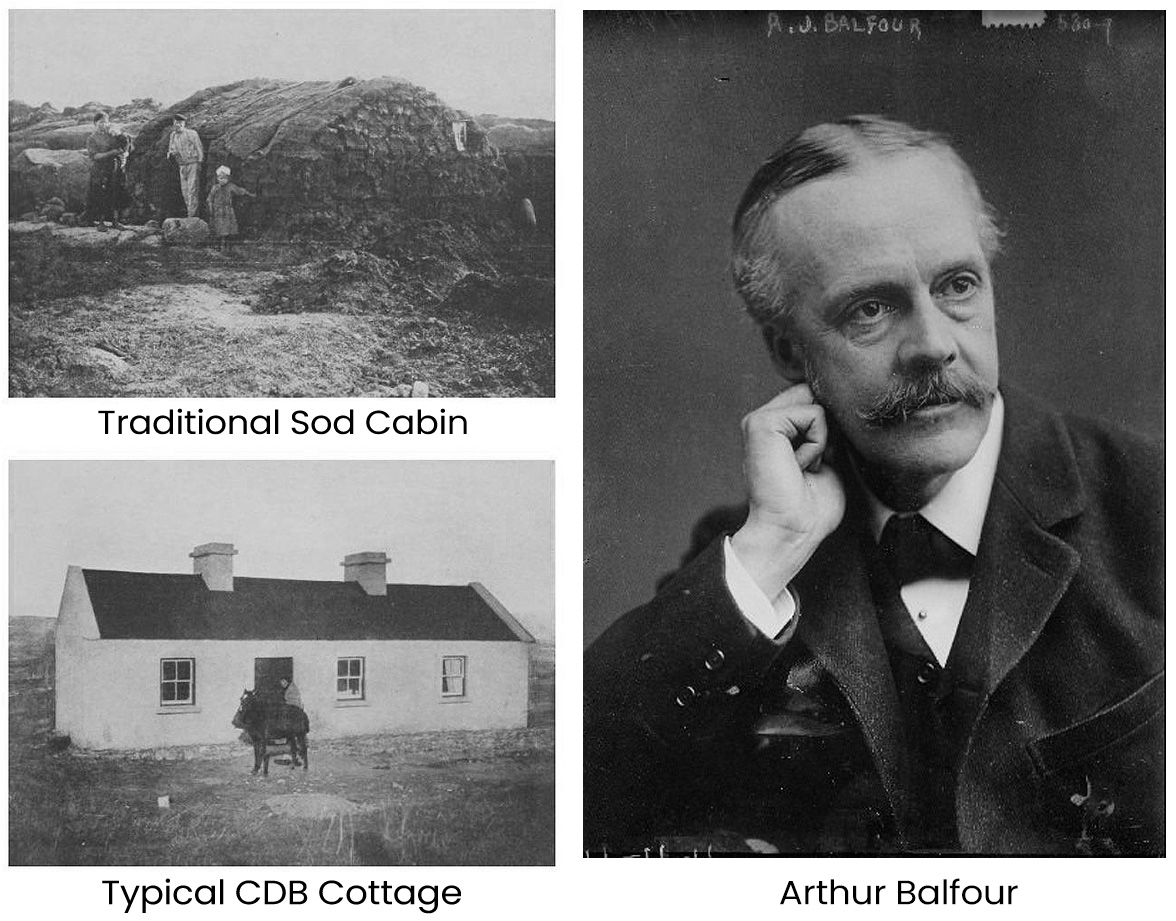

Established by Arthur Balfour under the Purchase of Land Act of 1891, the Congested Districts Board was a government body whose purpose was to alleviate poverty, overcrowding, and economic stagnation in the west and northwest of Ireland.

Mainly the CDB focused on land reform. Their activities (which in many cases proved ineffective long-term without government subsidies) included home building, the restructuring of failing farms, promoting local industries , improving livestock, and supporting fishing infrastructure through building piers and providing boats.

Coordinated by the CDB, fishermen and their wives from other regions of Britain and Ireland traveled to the Aran Isles to train the islanders in better fishing and fish-processing skills. They brought with them their own knitting traditions to share.

In other parts of Ireland the CDB had promoted the development of local cottage industries such as lace-making and weaving. It seems the idea now was to give Aran women a means of making money as well as producing protective clothing for their families.

With their new knowledge, enterprising local women began developing a unique style of jumper; one suited to the harsh Atlantic environment. They used thicker wool, all-over cabling, and structural techniques such as saddle shoulders. These innovations made the jumper more durable, comfortable and effective. For instance, the additional cabling added significantly to the insulation. The jumper was identical front and back so it could be put on quickly. The cuffs were simple and tight fitting - easily repaired after long hours of hard use.

Unlike many CDB intiatives, the Aran Islands knitwear industry took off, though slowly.

Do Aran Isle Knitting Patterns Represent Families?

No. Sorry to burst that bubble but let me explain.

We have already established that the Aran sweater as we know it is not an ancient artform. Its romantic overtones began to develop very soon after its invention at the turn of the 19th century.

Dead Sailors Tell No Tales, Actually

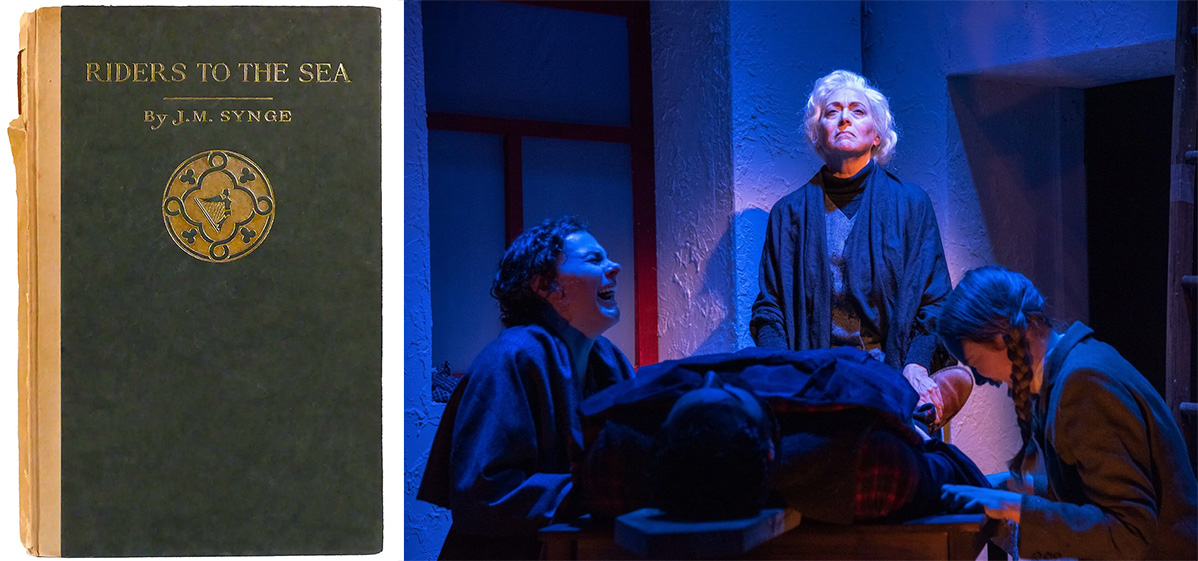

The “patient zero” for the various myths surrounding the Aran Isle Jumper was actually a play.

In the 1904 play Riders to the Sea by J.M. Synge, a drowned sailor is identified by his clothing. The play was a tragedy and a scathing rebuke of the harsh life on the Aran Islands, which had captured the attention of the public. The mother, Maurya, and her daughters identify the body of her last remaining son, Michael, through his unique, hand-knitted stocking.

Michael’s sister Nora says "It's the second [sock] of the third pair I knitted, and I put up three score stitches, and I dropped four of them".

Riders to the Sea was very popular and remains so today. Over the years, fans read into the body identification scene with wild imagination.

If you have ever heard the story that “Irish sailors’ families (or villages) used distinctive knitting patterns so that their bodies could be identified if they died at sea.”

This is where that came from. Period. There is exactly zero historical, archaeological or folkloric evidence for the Aran fisher families or villages ever engaging in such an organized practice.

Knitters simply knitted what they liked. Could some patterns have had familial associations simply because a mother taught her daughter a pattern she herself favored? Of course. But Ocham’s razor absolutely applies here. Remember also that the cottage industry was begun with an eye towards selling the jumpers to non-islanders. Therefore, patterns that proved popualr would certainly been replicated more often. (worth noting here that as I hunted for images of the Aran Islanders, I rarely found period photos of them wearing their own jumpers. I speculate that the bulk of the sweaters were made for sale and not actually kept at home)

Was Aran Isle Knitting Mystical or Religious?

Again, no. Some knitting patterns are believed, erroneously, to have religious meanings. This idea was fabricated by one Heinz Edgar Kiewe, a yarn shop owner who noticed a chance resemblance between Aran stitches and Celtic knotwork.

In 1967 Kiewe published a book, The Sacred History of Knitting, which popularized his suppositions surrounding European knitting in general and the Aran jumper. Presumably it sold well to tourists but has since been largely debunked.

You don't have to take my wod for it either. Check out Cable Crossings: The Aran Jumper as Myth and Merchandise by Siún M T Carden, a research fellow at the Centre for Island Creativity, Shetland College, University of the Highlands and Islands. Carden, and others, note that these symbolic meanings constitute an invented tradition; narratives constructed in the 20th century and spread through marketing and cultural writing, not well-documented historical practices.

Academic critiques note that while knitters and communities today may embrace symbolic interpretations, there is no evidence from the early history of the craft that stitches had codified meanings before these narratives were popularized.

***Please note that there will be some editorial opinion among the facts in the remainder of this article. I hope you will understand.

Aran Sweater Stories - Fun Or Fraud?

It is not hard to debunk the myths that have grown up around the Aran jumper. So why don’t people know the truth? How do these stories stay alive?

Profit. Modern sweater sellers have long perpetuated the myths in order to entice customers, especially tourists. More elaborate businesses have carried the myth-making forward with a specific aim of attracting customers from the Irish Diaspora in the United States who are seeking genealogical artifacts.

For example, one online seller buys into the ideas invented by Kiewe saying:

"Celtic art and Aran knitting preserve Irish history in similar ways, incorporating patterns similar to those found at Neolithic burial sites, and each carries a unique meaning. The cultural importance of these symbols and designs can be seen in centuries of Celtic art, and the famous Book of Kells contains some of the iconic patterns still in use today."

The most recent, and in my opinion most egregious, example of this trend is the specific marketing of family name cable patterns. The choices seem to be entirely arbitrary and there is zero evidence of this ever having been an Irish tradition, let alone an Aran Isles one.

In fact historically, the Aran Islands (Inishmore, Inishmaan, and Inisheer) have been dominated by very specific native clans. Records from the 1890s show the most common names to be Flaherty (Ó Flaithearta), Faherty (Ó Fatharta), Conneely (Ó Conghaile), and Derrane (Ó Direáin). Those who did have differing names, a small percentage, were most often married in. For example one fisherman who drowned in an accident in 1891, Patrick Dirrane, left a dependant widowed mother by the name of Honor Kennedy.

Therefore to imply that an Aran Isle sweater pattern "traditionally" belonged to say, the Andersons, the Boyles or the Hamiltons is patently ludicrous. One retailer flatly states:

“Over the years, in line with ancient Irish folklore, many Clans adopted the Aran Sweater as the ultimate Clan symbol. Historically these patterns were safeguarded within families and passed down from generation to generation.”

This is wholly unsubstantiated. And one might even say it is offensive as it ignores historical facts as well as the actual tragic story of the Aran Islanders.

In the opinion of this writer, it would be far more forgivable if the vendor acknowledged that they invented the idea. Simply and clearly say something like, “we were inspired to develop this new line of products, we hope you will enjoy them as a new way of expressing your heritage.”

Is it Acceptable to Have New Traditions of Celtic Dress?

Actually, yes. Very much so.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with a new tradition. IF it is readily acknowledged as such. Whether an idea sticks and becomes one depends on two things: A. Is it a genuinely good idea? B. Does it gain popularity and use organically?

For example consider the Irish County Tartan Collection offered by the House of Edgar Tartan Mill. First introduced in the 1990s, these designs have become extremely popular with American kilt wearers with Irish heritage (and beyond since they are quite beautiful, frankly). However, at no time has HoE or anyone else tried to claim they are ancient or have legends associated with them.

Fabricating tradition and history is, for lack of a better word, cheating. It muddles the historical truth, can lead to unfortunate oversimplification, and result in disappointment for the individual when they find out they have been played.

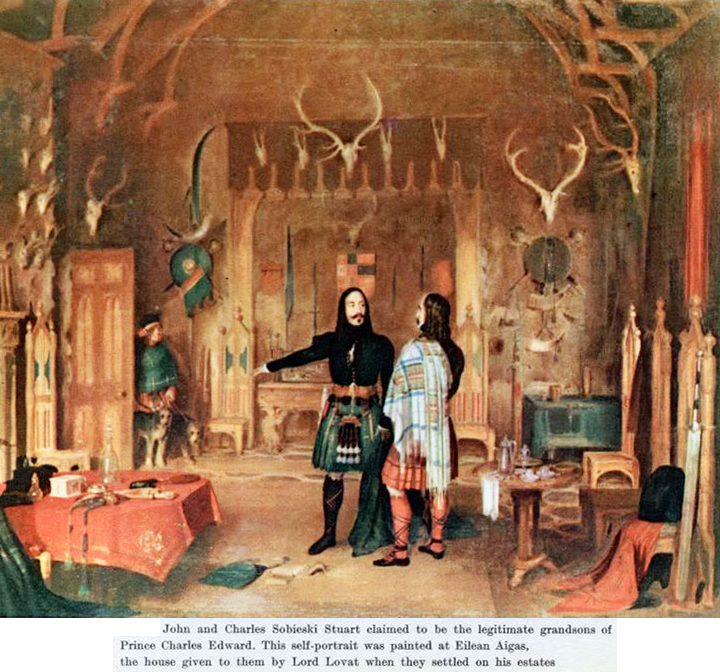

Sadly this is nothing new. In the Scottish world we can go all the way back to the infamous Sobieski Stuart brothers; two English conmen who claimed to be descendants of the Bonny Prince Charlie. Their scam was to create a selection of tartans which, they assured everyone, had been preserved in an ancient secret manuscript and were the traditional tartans of the various Scottish clans.

Their 1842 Vestiarium Scoticum was not confirmed to be a con-job until some time after its publication – and after several clan chiefs had bought into the romance and designated entries in the book as official clan tartans. In the intervening years, some clans rejected the Sobieski tartans and shifted to other patterns.

However, many retained them. They knew it had been a con, but decided they didn’t really care. The fact did not detract from their appreciation of the design itself. More so it was a case of “why bother looking for something else that may or may not even exist when this one works?”

A happy pragmatic ending. Maybe the clan-name aran sweaters will eventually go the same way.

Scotland has dealt with the problem of so-called “invented tradition" for a long time. The definitive work in the subject is 1983’s The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger. (Something for another article) As a society and culture, Scotland has had to adopt or slowly reject individual elements that felt “off” to succeeding generations.

But at least it seems most of the old invented elements of Scottish culture and Highland Dress were created out of zeal by people like Sir Walter Scott and the Victorians, not as retail business models. That is to say, while some of it may have been wooly-headed romanticism, it was not cynical.

Tartan mills like Wilsons of Bannockburn responded to rising consumer demand and current fashion trends with new products everyone knew were new. The motivations of the customer may have been based on false beliefs or myths, but the items purchased were just objects made to a desired aesthetic. Nothing more. No invented backstory.

If You respect a Culture and It’s History, Shouldn’t you tell the truth About It?

It is my assessment, as someone who has been in this scene and market for over seventeen years now, that the Irish family knit patterns are indeed cynical. It saddens me to think that someone might purchase such an item and believe they have the final truth of their heritage in hand; letting go of any desire to dig deeper and get at the rich authentic history of their ancestors.

History, culture and genealogy are not fields where simple answers tell the truth. Creating a false narrative for your product is preying upon the emotions of your customer - not validating those feelings. I am proud to say that this does not happen where I work at USA Kilts. If you ever have a question about anything we sell, please do not hesitate to contact us and we will give you all the information we can.

As for the Aran sweater, it is a truly magnificent creation anyone can enjoy. The next time you put yours on, maybe give a thought to the long-suffering, and largely forgotten people who created it. That which is remembered lives.