The Saga of the Scots-Irish in Appalachia

Poverty, famine, a dream of freedom….these things drove scores of people from Ireland to the new world. But I’m not talking about the blight and the desperate masses flocking to New York, Boston or Chicago.

The Irish poor I am talking about came to our shores over 300 years ago. And the place they found refuge was the misty mountains of Appalachia. This is their story.

The saga of the Scots-Irish of Appalachia begins way back in 1603 with the ascension to the throne of King James the VI of Scotland, James I of England.

James was a hugely important figure in the history of the British Isles. It was he who created the ‘United Kingdom’. England and Scotland were relatively easy to officially merge politically. It was a done deal as soon as James became ruler. But James wanted more. More permanence. More stability for a lasting Protestant kingdom. He implemented a number of changes and new laws. Much of which involved promoting the Anglican Church as the official state church throughout his realm.

But then there was Ireland. Parts of Ireland had been possessions of the English crown since the late 1160s when Anglo-Norman barons invaded and carved out fiefdoms. In 1171 King Henry II claimed dominion over the island though it was actually pretty tenuous, not really real.

Much later, in 1541, Henry VIII was proclaimed King of Ireland by the Irish Parliament and entered a long-running war with the Gaelic chiefs. Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth I, inherited the quagmire.

Henry and Elizabeth had good reason to both fear, and seek control over, Ireland. The Catholic Gaels, besides fighting the English themselves, would also happily harbor Catholic enemies from abroad, especially Spain. For the Brits it felt like a dagger being held to the throat.

Then in 1593 a hotter conflict called Tyrone's Rebellion, or the Nine Years War, erupted. This pitted a confederacy of Irish clans, backed by the Spanish, against the Tudors. By 1603, the Irish were defeated and many rebel Ulster lords fled the country leaving their lands to the English.

For James I, this was a great opportunity. What followed was a period called the Plantation of Ulster that lasted from 1605 to 1697.

It was a series of organized settlements in Northern Ireland. Technically, this was not the first time such a scheme had been attempted, but it was the most effective and long-lasting. The British Crown offered land grants to anyone willing to settle in the counties of Antrim, Down, Armagh, Tyrone, Donegal, Cavan, Fermanagh, and Derry.

For many Scots, particularly from the Lowlands, this seemed like a golden opportunity to improve their economic situation. For many it also promised greater religious freedom. While the United Kingdom was officially Protestant, the early Presbyterians were often discriminated against.

As many as 200,000 Scots crossed the North Channel to settle in Ulster during this 90-year period. By the 1630s, there were 20,000 adult male English and Scottish settlers in Ulster, which implies the total settler population could have been as high as 80,000 to 150,000.

It should be noted that this was all technically based on personal initiative. While the British Crown encouraged and co-operated with the immigrants, it was fully a private venture. Landlords were in it for the profit.

But Ireland was not as “free” for the newcomers as they’d hoped. The majority lived as sharecroppers working the estates of landowners. They could not own land and they had no political voice. And ironically, though many came seeking religious freedom, they were required to tithe to the Anglican Church. At the same time, a unique form of Gaelic culture was sprouting as the new Ulster residents intermingled with the native Irish.

In the 1690s a famine caused a new wave of Scottish immigration to Ulster which resulted in Scottish Presbyterians becoming the majority community. However, despite their numbers they were often the victims of discrimination and still denied political power. Population pressure and the greed of landholders caused rents to skyrocket. Meanwhile resentment of the Church of England was as bad as ever.

Many began contemplating moving to a land that promised both economic opportunity and real religious freedom - North America. Starting in the early 1700s, the group that would come to be called the Scotch-Irish or Scots-Irish began migrating to the New World in large numbers.

The first immigration of 1718 was only about 700 people, mainly Presbyterian farmers and merchants from the Bann and Foyle Valleys of Ulster. The Bann Valley group settled in the frontiers of Maine and New Hampshire while the Foyle Valley group settled in Massachusetts.

These were the first but not the last. By the decade’s end, 2,600 more had arrived in New England. Others arrived in Virginia and spread out across the Carolinas. Before the American Revolution, more Scots-Irish emigrated to the continent than almost any other group. By the 1770s, an estimated 250,000 individuals lived in the American colonies.

However, the majority of Scots-Irish were subsistence farmers. Like other immigrants, they were lured to the New World by the promise of cheap land. But more so they sought a degree of isolation so as to practice their religion in peace and avoid the landlords.

This made the frontiers of the colonies especially attractive. Anywhere the white man was pushing into Native American land, anywhere resources were thin, the soil difficult to work or the weather harsh, the Scots-Irish found a home. In fact, many colonies actively recruited these immigrants offering the desperate newcomers cheap frontier land in hopes of creating a buffer between colonial civilization and hostile indigenous tribes.

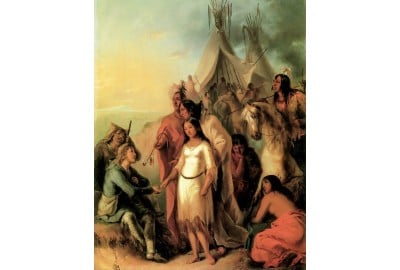

And nowhere did this work out better than in the southern Appalachians. Here the Scots-Irish thrived in a humble but sustainable lifestyle. They also developed close relationships with Indigenous peoples, often including intermarriage.

One major arena for cooperation was game hunting and the fur trade. Scots and Scots-Irish often made a living as long-hunters and trappers - harvesting deer and beaver hides to sell in the cities. The beaver trade was biggest in the north while deerskin was most common in the south. Gaels traded and worked alongside tribes such as the Creeks, Cherokees, and Choctaws throughout the eighteenth century. And this is partly why so many Americans today can trace their ancestry back to both Gaelic and Indigenous peoples.

One great example is James Adair (1709-1783). Born in County Antrim, Ireland, his ancestors lived in both Ireland and Scotland. Like many Scots and Scots-Irish of later generations he left numerous offspring among the Cherokee. Although Adair was considered a diplomat and a peacemaker among the southern tribes, he is remembered primarily as a recorder of indigenous history. Adair’s History of the American Indians published in London in 1775 is considered an invaluable account of tribal manners, customs and language even today.

Scots-Irish immigrants played a strong role during the Revolutionary War too. Just one example is the battle of Kings Mountain, South Carolina, October 7, 1780. Descendants of Scots-Irish immigrants to Tennessee and Virginia were instrumental in defeating Loyalist militia forces. Thomas Jefferson later called the battle "The turn of the tide of success."

So where are the Scots-Irish today? All over the country, frankly. However the home of the culture they created is still of course Appalachia.

For instance, today, North Carolina has the largest percentage of Scots-Irish ancestry of any state, with 2.9% of the population claiming the heritage. South Carolina and Tennessee follow at 2.4%.

The isolation, and frankly the poverty, of Appalachia made for a unique distillation of elements.

Appalachian quilts tell stories in each design. Appalachian foods like chow-chow, hoecakes, chicken fried steak, biscuits and gravy and fiddleheads are loved by millions, not to mention Appalachian moonshine!

(just remember, if you pay taxes on it, it ain’t ‘shine)

Appalachian fiddle music and blue grass lifts us up and connects people directly to generations long gone. Buck dancing echoes the Irish folk dances of 300 years ago.

And there’s a certain attitude. We Americans like to think of ourselves as no-nonsense, pragmatic, honest, down-to-earth, and just a touch suspicious of authority. I won’t say the Appalachians invented that, but they sure as heck live it. Supporting your family by going down a coal mine every day will do that. And that sense of mutual aid, of putting family and community first, is absolutely something they inherited from their Gaelic ancestors.

So if you’re of Scots-Irish descent, stand proud. If you love Appalachian culture, I hope you’ll consider learning more about its diverse roots.