The Truth Behind Kilts, Kilted Soldiers and Bagpipers in World War One

“. . . don’t grieve, there are worse deaths than leading a platoon of Highlanders into action.”

– Lieutenant C.B. Anderson on foreseeing his own death

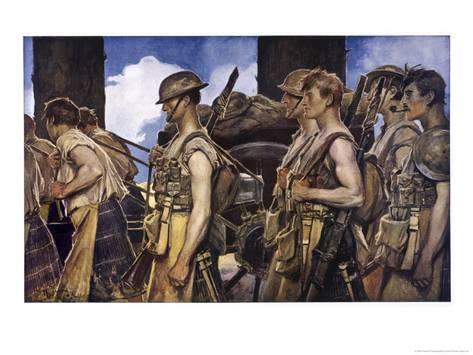

We’ve all heard of the so-called “ladies from hell” - the famous epithet given to Highland regiments in the first world war. However this term and the images it conjures barely touch on what it was like to be a Scottish regimental soldier in the Great War. Just like other men in uniform, the Highlanders experienced a living hell that snuffed out lives indiscriminately. The friend you’d just had breakfast with an hour ago, could be dead in your arms in the blink of an eye. Yet the valor of the Highland troops, and their impact upon the morale of the Allies, is undeniable. Here are some essential facts and the truth behind some of the myths.

Who Called Kilted Soldiers in World War I “Ladies from Hell’?

It may come as a surprise, but there is no proof the Germans ever called the Scots ‘Ladies from Hell’ or ‘Devils in skirts’.

Yes, the Germans were afraid of the Scottish troops, who had a reputation for tenacity and fierceness in battle. However, this was not universal or necessarily more potent than the fear engendered by any wave of men advancing with rifle and bayonet.

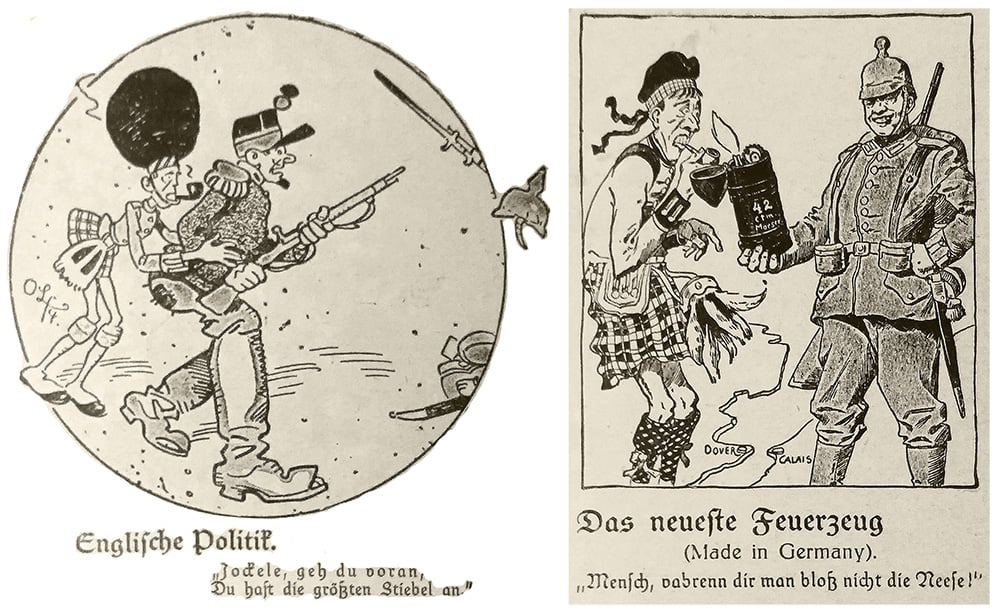

No written records, either personal or journalistic, have been discovered to suggest ‘ladies from Hell’ was a German thing. To the contrary, German propaganda often poked fun at the kilted troops. One especially impactful example is a commemorative cast-iron medallion showing the figure of 'Death as a Scottish Piper'. It was cast in 1915, probably after the battle of Loos in which Scottish regiments suffered heavy casualties.

No written records, either personal or journalistic, have been discovered to suggest ‘ladies from Hell’ was a German thing. To the contrary, German propaganda often poked fun at the kilted troops. One especially impactful example is a commemorative cast-iron medallion showing the figure of 'Death as a Scottish Piper'. It was cast in 1915, probably after the battle of Loos in which Scottish regiments suffered heavy casualties.

Modern romantics can easily see this image as “bad ass”. A representation of the unearthly courage and power of the Scottish warrior spirit. However the truth is not glamorous - the image commemorates a German victory by picturing what the soldaten saw as foolish suicidal behavior. That is, the bagpipers and their fellows marching out of the trenches to their doom, all clad in archaic, impractical battle gear.

German Propaganda Medalion 1915

So who DID invent the idea of the Ladies from Hell?

The noms de guerre ‘ladies from Hell’ or ‘devils in skirts’ rather seems to have been coined by Allied troops, journalists and artists. It was never formal propaganda but seemingly more of a collective myth; folk-etymology. A paper presented at the ‘Languages and the First World War’ conference hosted by the University of Antwerp and the British Library in 2014 notes that:

“...to date no documentation in German, in newspapers, letters, diaries, memoirs or anywhere else, supports this. It is entirely a story reported, and reported vigorously, by Allied soldiers, via newspapers at the time…”

The earliest recording of the epithet comes from a 1915 account of Canadian Highlanders at the Ypres salient. It was repeated often in newspapers. (only a third of which were Scottish - some Scottish soldiers apparently referred to themselves as “Harry Lauder’s Idiots” in typical rye humor).

Soldiers of course loved the name and would always repeat it to the press. It truly was a great morale boost. The term was truly cemented in the popular imagination by post-war memoirs. For instance, in The Daredevil of the Army (New York, 1918) A. Corcoran wrote that it was, “the pretty compliment they earn from their enemy, in whose souls they are inspiring real terror.”

An unusual example appears on page 212 of The Gates of Janus by William Carter (New York, 1919), a memoir of the war written in the form of an epic poem:

Cambrai has fallen! Great St. Quentin too!

On thirty-five mile front they’ve broken through

Haig’s “Kilties,” called by Hun: “Ladies from Hell,”

Push now to end what’s been begun so well!

What Were Kilted Soldiers in Wolrd War I Really Like?

Were the Scottish troops more reckless? More fierce? Very possibly. Historian Niall Ferguson compiled the following casualty statistics for the percentage killed of all men mobilized in the war:

- Britain and Ireland – 11.8%

- British Empire – 8.8%

- Scotland – 26.4%

- France – 16.8%

- Turkey – 26.8%

- Serbia – 37.1%

- Germany – 15.4%

These numbers can be interpreted many ways, but they do imply that the Scots, by dint of their martial culture or by the poor choices of their commanders, were more likely to perish.

“Highland” soldiers had a mixed reputation for toughness, bravery, recklessness, insubordination, alcoholism and viciousness. For example:

“Two Kilties caught a German who shouted for mercy and said he was a Christian. The fellows said, ‘Alright, you’ll be an angel tomorrow,’ and bayonet him. Other 2 caught 2 officers & 4 men who were asking for mercy; they: ‘By ----you’ll get mercy this time,’ and bayoneted the lot.”

However the negative, stereotypical traits ascribed to the Kilties have been largely debunked. Thomas Greenshields in Those Bloody Kilts: The Highland Soldier in the Great War (2022) offers a very complete picture of what life was like for the kilted soldier and reveals how the lads in the Highland regiments, when not charging across No Man’s Land, were not much different from their counterparts in other units. As Sherman said "War is all hell" and brings out the best and worst in men.

The Soldier’s Kilt - Fashion and Swagger

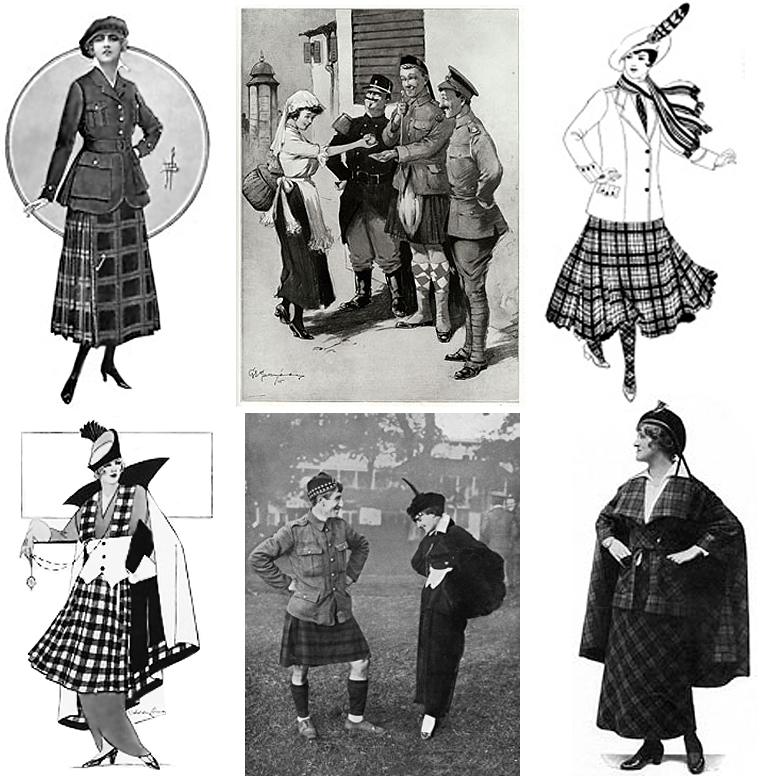

There is no denying that, just like today, the kilt made a huge impact on anyone who saw it.

In his 1918 war memoir The Fifty-First in France Robert Ross wrote, “The natives were all agog with excitement to acclaim the “ladies from hell.”’

Similar though not flattering, is the observation of Pte R G Hill from 1914:

"The highlanders in our brigade caused much amusement, the female part of the population shrieking with laughter at the dress of the 'Mademoiselle Soldats'.”

The kilt was exotic and titillating as always. Then as now, jokes and speculations about what the men wore under their kilts was common. However, the bemusement at what seemed like a silly gender transgression usually turned to admiration.

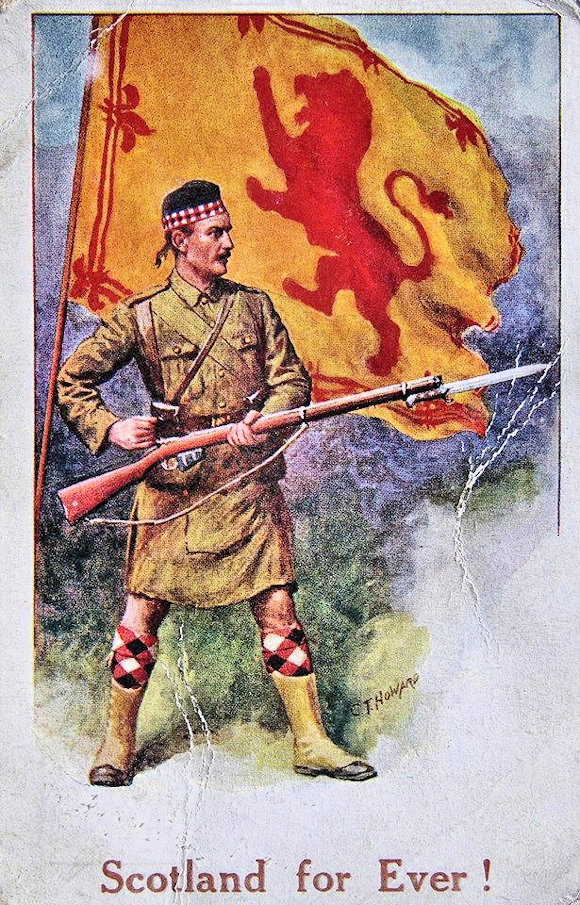

Whether they actually were or not, Scottish regiments that wore the kilt had the air of being elite forces. The garment drove home the idea of the virile and aggressive Highland Warrior. George Macdonald Frasier, author of the Flashman novels once quipped that the Highland regiments were “Queen Victoria’s own barbarians.” This persona persisted all the way from Waterloo, through the Crimea, and into 1914. As in the past, the kilt inspired confidence and boosted morale for citizen and soldier alike.

In time, the Scottish troops made such an impact in France that the fashionistas of Paris even began incorporating tartan and British military flair into their designs. At the same time, the ladies of France seemed to give special attention to the Scottish and Canadian boys in kilts. This can be seen in pop art and photography of the period.

Meanwhile at home, recruitment drives targeted Scots by bidding them to fulfill the martial legacy of their forefathers. It worked very well. As is the case in all nations, poverty and a lack of opportunities inspired young men to join up. Patriotism was strong, yes, but the chance to escape poverty and to be somebody was key.

The allure of the storied and mighty Highland regiments worked equally well with non-Scots. Initially recruitment centered on “home” regions of Scotland. For instance the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders primarily recruited from Argyllshire, Bute-shire, Clackmannanshire, Dumbartonshire, Kinross-shire, Renfrewshire, and Stirlingshire. However Highland depopulation prior to the war meant pickings were slim. Recruitment soon had to expand into the Lowlands and even other parts of Great Britain such as northern Ireland. Losses also led to the inclusion of English battalions within Scottish divisions to maintain unit strength. Meanwhile, something like 45% of Scottish recruits ended up in units which did not have direct Scottish roots.

The takeaway is that the power of a kilted regiment lay not in the family origins or genetics of the men so much as in the culture of the unit itself. The internal traditions, the shared stories, the accomplishments emblazoned on the regimental banner…all this helped form raw recruits into soldiers with a unique sense of self and a belief in their own capability. A standard to live up to. Kilts and bagpipes certainly played a big part in this acculturation.

What Did Bagpipers Do In World War I?

The impact of the kilt on morale really went hand in hand with the use of bagpipes.

Historically the great Highland pies had been used as both a signaling device and a means of boosting the morale of Clansmen charging into battle. While outmoded in the former role, the latter was long maintained by the British army.

While it did not occur nearly as often as we like to imagine, there were plenty of instances, such as at Loos, of troops going ‘over the top’ preceded by one or more regimental pipers.

Sir Philip Gibbs, an official British reporter, wrote that it was “the most awful music to be heard by men who have the Highlanders against them, and with fixed bayonets and hand-grenades they stormed the German trenches.”

A regimental piper would climb out of the trench just before the rest of his unit and play “the charge” which could be any number of traditional tunes. Standing in full view of the enemy and armed with only his pipes he would continue playing, often marching back and forth along the line, for as long as the assault lasted. Ideally if he was shot, another piper would come out to take his place.

This behavior perplexed the Germans who alternately saw these men as either brave or utterly mad. It is hard to say just how much the piping affected their morale or discipline, but clearly the Germans knew that the eerie pipes heralded the advance of deadly rifles and bayonets.

The pipes did give the Allied troops a boost. In 1993 Harry Lunan, the last WWI piper, recalled in an interview:

“You were scared, but you just had to do it, they were depending on you. In the first assault [at High Wood], I played the tune Cock o’ the North. I played my company over the bloody top, right into the German trenches. It was stupid as hell…Men falling all around me, falling dead…it was bloody horrible….[but] hearing the pipes gave the troops courage.”

This esprit de corps came at a horrible price. Of the 2,500 pipers who served during the war, an estimated 500 were killed while another 600 were wounded.

What Was Life Like in the WWI Trenches for Kilted Men?

Here’s a small taste of what daily life was like for one kilted officer. From the Diary of Corporal James N. Beatson No 2024. B Company 9th (Highlanders – ‘The Dandy Ninth’) Royal Scots. February – December 1915. 81st Brigade 27th Division (d. July 23rd 1916 Battle of the Somme - 51st Div):

Our dug-out, that is Watson and I, was only about 3ft high with a fireplace but we deepened it yesterday to 5ft and improved drainage etc, etc….

Today I’ve spent cleaning myself; just had a shave and a wash up, cleaned my rifle and bayonet and now Watson is trying to improve the fireplace and dry the floor with ashes and sand. We dug rather deeply yesterday and the water was squelching on the floor under the sheets this morning. It’s a nuisance lifting the tail of your kilt when you go in….

Our dug-outs being so verminous, the blankets haven’t been given us so we retire thusly [sic] – socks on, kilt loosened, jacket buttoned only at the waist, greatcoat turned upside down and legs slid into the sleeves. This leaves you to curl up and chew the mud off the end of the coat.

Opinions on the practicality of the kilt as combat dress varied widely. This was nothing new. The debate had raged in Britain for ages. A harsh critique of the kilt and Highland Dress uniform appeared in the Sterling Observer all the way back in 1850 entitled 'Editorial by soldier in an unnamed Highland regiment bemoaning the kilt as a uniform'.

The most outspoken advocate for the kilt as combat dress was Major General Douglas “Tartan Tam” Wimberley, CB, DSO, MC, commander of the 51st Highland Division. In his opinion, "Whether in peace or war, a regiment that parades in the kilt cannot be mistaken by friend or foe alike."

Wimberley also argued that the kilt offered superior freedom of movement and was better for the damp conditions of the trenches. Trousers, his side argued, once soaked in mud and standing water would remain wet and unsanitary which increased the risk of trenchfoot and other illnesses. The kilt allowed for beneficial ventilation. Meanwhile, the thickness of the wool wrapped around the torso lent insulation for the core.

The counterarguments were hard to dispute though. 16-18oz wool kilts caused chafing. Bad enough that some officers purchased silk drawers to wear underneath, a bit of a guilty privilege perhaps.

The bottom edge of the kilt could cut into the backs of a soldier’s knees, a fact made worse if a wet kilt froze. Such chaffing and abrasions could allow infection in. The kilt was apparently hard to keep free of lice. The kilt was more likely to catch on barbed wire than trousers. Worst of all, the kilt could not protect against Mustard Gas (sulfur mustard); a blistering agent that causes severe damage to the skin upon contact.

Be all this as it may, kilts continued to be worn throughout the war. However they were relegated to use only in warm weather. As early as the winter of 1914-15, kilted units were issued wool trousers to better deal with the cold. The kilt was then reissued as warmer weather returned in the spring.

Why Do Soldiers Really Wear the Kilt?

It seems very clear that, as Gen. Wimberley observed, the major reason to retain the kilt was for morale and esprit de corps.

In the aftermath of the war, this idea was derided as nostalgic and romantic. The kilt in combat seemed symbolic of the sort of wooly thinking that had led to the war in the first place. (Not unlike the French military concept of ‘elan’ which prompted their army to retain red pantaloons for some time) Such naivete seemed to have been proven old fashioned and downright dangerous. Romanticism washed away in blood and mud.

Indeed the combat kilt was phased out fairly promptly. However, like the bagpipes, it has been retained to this day for parade occasions and peacetime duties. Thus we see that the basic emotional argument made above seems valid.

The power of the kilt (and the pipes) is in its mere presence. The kilt is a touchstone for memory and identity. Men who wear the kilt in a military context do not do so on some whim of fashion. They wear it because it is a tangible connection to the legacy they represent as Highland soldiers. The justness of any one conflict might be debated. The value of goals achieved or lost weighed by historians with the benefit of hindsight. But for the average Jock (or Jennie) who has made the army their home, their life, there is the sense of family that can keep them whole even if facing Hell itself.

This is two-fold. It is the family of the now; their comrades. And it is the family of the past; those who wore the uniform for centuries before them. Those whose honor can not be forgotten and whose sacrifices should never be dismissed. And this is why soldiers wear the kilt.