Evicted By Force - The Highland Clearances in Scotland

People have always strived for progress. Our desire for the betterment of humankind is behind some of our most outstanding achievements.

But what happens when the cruel or callus in positions of power twist the meaning of “improvement” to fit their selfish needs? It's a tale as old as time; the fortunate exploiting the underprivileged. And one of the most tragic examples occurred from the late 18th century to the mid-19th century in Scotland. A time when families were torn asunder and forced off their ancestral lands while watching their homes destroyed in the name of progress.

Now the Highland Clearances is a deeply complex subject, so our plan is to set the stage, then give you two of the most egregious examples of what happened.

First of all, let’s look at what came before…the clan society of the highlands.

A clan was usually led by a chief. Originally an appointed head of the family, this position did become more and more hereditary over time. The rest of the kinfolk lived on lands held by the clan and organized into small agricultural townships. Pretty much collectives or joint-tenancy farms. The Croft was one such unit.

The chief owned the land and leased it out to "tacksmen," who in turn subleased the farms to tenant farmers or crofters. The crofters would employ workers or cottars to help cultivate a specific farm.

The Clan system was deteriorating well before the highland clearances. It had often come under attack. The Highlanders, being so far north and isolated, had always given those in power in the lowlands pause. As we know very well, the Highlanders were often at odds with the southern nobility. For instance, King James I was so terrified of any uprising that he systematically called clan chiefs into attendance at court. He hoped that putting physical distance between the chiefs and their kin would promote loyalty to the crown over chiefdom.

The friction between north and south was both economic and, after the Protestant reformation, also often religious. It led to the Uprisings of the 17th and 18th centuries when Highland clans supported the royals they felt would give them the better deal and preserve their freedoms ie. the Stewarts. This all came crashing down after the defeat of The Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1746.

After Culloden, rebellious Highlanders were explicitly targeted. Laws were established to diminish the influence of clan chiefs and Gaelic customs. Under the Heritable Jurisdictions Act in 1746, men who refused to swear a loyalty oath to the Hanoverian government found their land put up for auction. This allowed Lowlanders and Englishmen to purchase large swaths of the Highlands.

However, many new landowners found these purchases not particularly lucrative. Clan-style organization and land use was diffuse and vague. It had always been designed simply to maintain a reliable subsistence for the local population in a harsh environment. Profit, expansion, or upward money flow had little to do with its core.

And to “modern” outsiders this just seemed backward. How could you make the Highlands profitable? Was the question of the day.

Enter one Sir John Sinclair.

Did The English Cause The Highland Clearances?

From all accounts, Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster (1754-1835) was not predatory. Rather, he was a progressive mercantilist in the mode of John Lock. Sinclair believed the solution to improving farming and the standard of living in the Highlands was trade.

Sinclair, born in Thurso Castle into a branch of the Sinclair Earls of Caithness, a landowner, politician, early improver, agriculturist, statistician and ambassador for his country, not to mention an MP. He was the first president of the Board of Agriculture and founded a society for the improvement of British wool. In 1805 Sinclair was appointed commissioner for the construction of roads and bridges in the north of Scotland and supervised the compilation of the first Statistical Account of Scotland (1791-1799).

As Sinclair saw it, the most powerful tradegood in the British empire at this time was wool. Everyone needed it - at home and abroad. If the Highlands could produce it, the land would become prosperous and everyone would benefit.

However, the old-fashioned farms up there didn't house large numbers of sheep. The climate was considered too harsh for the animals. Sinclair proposed that the Highlanders change the breed of sheep they kept. His research suggested that the Cheviot sheep, found commonly along the border of Scotland and England, would be a perfect specimen for adapting to the wind-swept climate of the Highlands.

The first attempt at importing and raising Cheviots was an immediate success with 100% survival of Sir John’s imports. The next step was to slowly introduce the wool from these sheep into the highland economy through considerate and measured changes.

Sinclair proposed that tenants on small holdings maintain possession of the area while also pooling their resources together. In this way they could build their investments with larger herds over time. At the same time, gradually expanding grazing areas. The result would be a slow long-term return on the sheep with the monetary gains split between landowners and tenants.

But Sinclair’s scientific plans fell on deaf ears. Instead, landowners hemorrhaging money in the highlands heard one message - Cheviots work. More land plus more sheep equals more profit. Sinclair had inadvertently started a wildfire.

The real equation became more land plus more sheep minus people.

After all, you only needed a few shepherds and you could pay them a pitance. Any other land use was just a drain! Rent from poor tenants could not compete with wool profits.

The first clearances began in the 1780s and the trend grew throughout the era of the Napoleonic wars.

Most landlords simply sought to retain their tenants but re-deploy them to the unprofitable fringes of their estates - especially coastal areas where they would work the fishing and kelping industries. It was only later that the landlords simply evicted people without concern for where they ended up.

What Did The Duke Of Sutherland Do To The Crofters Living In The Highlands?

One of the earliest and most egregious examples of the clearances occurred on the Sutherland estate between 1809 and 1821.

This one million acre estate was owned by George Leveson-Gower, thanks to his marriage to the then Countess of Sutherland. Initially the estate had removed a small number of tenants with an eye towards cutting out the tacksmen. When the new Duke of Sutherland took control, he launched a series of considerable "improvements" - the common term used by the landlords.

Several agents were employed to carry out evictions. The most efficient, and notorious, were William Young and Patrick Stellar. Patrick Stellar was a Scottish man with distant relations to the Sutherland estate, but neither he nor Young spoke a lick of Scots Gaelic.

This was apparent at the beginning of their evictions in 1813 when men from Clan Gunn came to Golspie to protest the arrival of massive flocks of sheep. Young met them with a force of lackeys to break up what he called a "mob." None of them spoke Scots Gaelic, so the Gunn farmers were more perplexed than afraid.

As things heated up, Young used his clout to call in British army troops from Ireland. Ironically, their experience with being on the reverse of this situation, when Scottish-born troops had suppressed Irish gatherings, made them ideal as enforcers.

The threat of violence sent a clear message to Clan Gunn: Leave without trouble or else.

In December of that year, tenants from Strathnaver journeyed to Golspie to hear their eviction notice. This time, Young employed a local minister, Davide Mackenzie, to translate. Mackenzie also supported the evictions through his preaching - warning tenants that they would face fire and brimstone if they resorted to unlawful resistance.

Of course, during these sermons Mackenzie never divulged the sums of wealth he was receiving, or the origin of the brand new pulpit his church received.

An auction for the soon-to-be-vacated land was set to occur after the notice. However, only one person placed a bid. This being none other than Patrick Stellar, the other agent in charge of evictions. This was his second purchase of land on the Sutherland estates, and he planned to collect.

Often during the clearances, that land was set to fire. This for two reasons. First, it cleared the land for sheep pastures. Second, it insured the tenants would have no home to return to.

In the early days of the clearances many tenants would partly dismantle their dwellings for supplies to build new homes on the coast. But things were slightly different at Strathnaver in 1814. Evictees were forbidden to dismantle their homes. Instead, estate enforcers stripped them for fire fuel. Now, Stellar did pay the tenants for the wood, but the price was entirely set by what Stellar saw fit.

The Strathnaver tenants who had not fled by this point had enforcers sicced on them. Eyewitness accounts record people being chased from their homes even as Stellar and his men set them on fire.

One example…William Chrisholm had a hut in Strathnaver that his Daughter-in-law, Janet Mackay, lived in with her mother Margaret. Margaret was a frail, sickly old woman. When the officials came and started setting dwellings on fire, she could not move. We don’t know if the men were fueled by their domination over the town or were simply not paying attention. But they set fire to Chrisholm's hut with Margaret Mackay still inside. Janet and her neighbors fought the fires to save Margaret, but she succumbed to her burns a few days later.

A stonemason, Donald MacLeod, who claimed to have been living in Strathnaver when this occurred, later wrote, "Every imaginable means short of the sword or the musket was put in requisition to drive the natives away, to force them to exchange their farms and comfortable habitations, erected by themselves or their forefathers, for inhospitable rocks on the sea-shore, and to depend for subsistence on the watery element in its wildest mood…The country was darkened by the smoke of burnings, and the descendants were ruined, trampled upon, dispersed, and compelled to seek asylum across the sea."

MacLeod recounts the long trek the beaten and exhausted tenants endured, pointing to only a few children surviving the trip. Deaths never brought to light in any official documents.

Two years later, Patrick Stellar would be tried for Maragaret Mackay's death and the other injuries and deaths caused by his fires. There was quite a bit of witness testimony against Stellar. His defense gathered the statements of other officials present at the burnings defending their tactics. In the end, the judge found Stellar innocent. Ruling he was merely performing his duty as the authority of the Sutherland Estate, evicting the land in the name of agricultural progress.

According to John Prebble, the judge had this to say: "...if the jury had any difficulty in striking the balance, then they must take into account the character of the accused. The implication was clearly that against the word of a man so nobly commended as Patrick Sellar, of what value was the evidence of a card, a thief, or a bigamist?"

And so Stellar was free to return to his new estate in Strathnaver, where he continued to carry out evictions on any tenants still left in the area to expand his ever-growing sheep pasture. His only change in behavior after this ordeal was waiting to burn homes until after the tenants were evicted.

Now remember. This was just one town on one estate during the highland clearances. Clearances from the Sutherland estate went from 1811 to 1821. It's estimated that 15,000 people were removed from their land to make room for 200,000 sheep.

Where Did People From The Highland Clearances Go?

Most of the evicted tenants set up new townships in the coastal regions of Scotland. Here they eked out a living through fishing and kelp farming. However, over time kelp prices dropped and the population grew as soldiers returned from the Napoleonic wars. Reconstruction would be a slow, tedious process.

With poverty on the rise, the crofters were about to be hit with another insurmountable problem: the potato famine. Landowners were made to pay famine charity to the displaced crofters still on estate-controlled lands. Suddenly no one in Scotland was prospering. And a new wave of clearances was just about to begin.

Crofters with fortitude and ability began moving to the lowlands where they could find industrial jobs. Other crofters went into indentured servitude to avoid starvation. Landowners became wise to the idea that it would be cheaper to fund sending crofters abroad than it would be to continue paying charity funds.

And in reality, many weren't given an option. For example, a Scotsman, Colonel John Gordon, acquired land in the Outer Hebrides from Clan Ranald when the chief went bankrupt in 1838. When the famine hit, Gordon earned less than 66-percent of his investment while paying for famine relief.

He turned to forced emigration to solve his financial issue. For example, in 1851 the small township of Balnabodach, with less than 30 people, was marked for clearance. Hired thugs ran through the township and dragged the tenants to the harbor and from there ferried to Lochboisdale.

Once there, the tenants were coerced to attend a public meeting. It was said that anyone failing to attend was tracked down by dogs and made to pay a fine.

At the meeting, the tenants were informed they were going to Quebec, Canada. But they were assured that good living conditions and jobs awaited them there. Many would board the waiting ship, "The Admiral", willingly… full of hope.

Gordon's agent in charge of this endeavor, John Fleming, cleared thousands of people by this method. Fleming claimed that everyone going would be met on the shores of Canada by immigration services and provided with farmland. This was a bald-faced lie, as evidenced by letters between Fleming and the chief immigration agent in Canada, A.C Buchanan.

Sometimes Fleming didn't bother to inform Canadian agents until the ships departed. Buchanan writes that all parties on the boat were impoverished. Many have insufficient clothing. Little, if any, spoke French, the native language of Quebec, so employment could not be provided. These immigrants would be forced to trek to other parts of the country for work.

Buchanan informed Flemming that the Canadian government could not afford to carry freight of "those who are interested in the removal from Great Britain of paupers and other unprofitable portions of the populations"

He warned that if Gordon continued, he should expect to see no continued success or progress for his evicted tenants.

G.M. Douglass, the medical superintendent in Quebec, wrote, "I have never, during my long experience at the station, saw a body of emigrants so destitute of clothing and bedding; many children of nine and ten years old had not a rag to cover them."

The forced evictions from Gordon's land concluded that year. He had cleared more than 2,000 people from the Outer Hebrides on five ships. Of the 1,700 transported to Lower Canada; only 600 were accepted as paupers and supported by the colony. The rest were reduced to beggary.

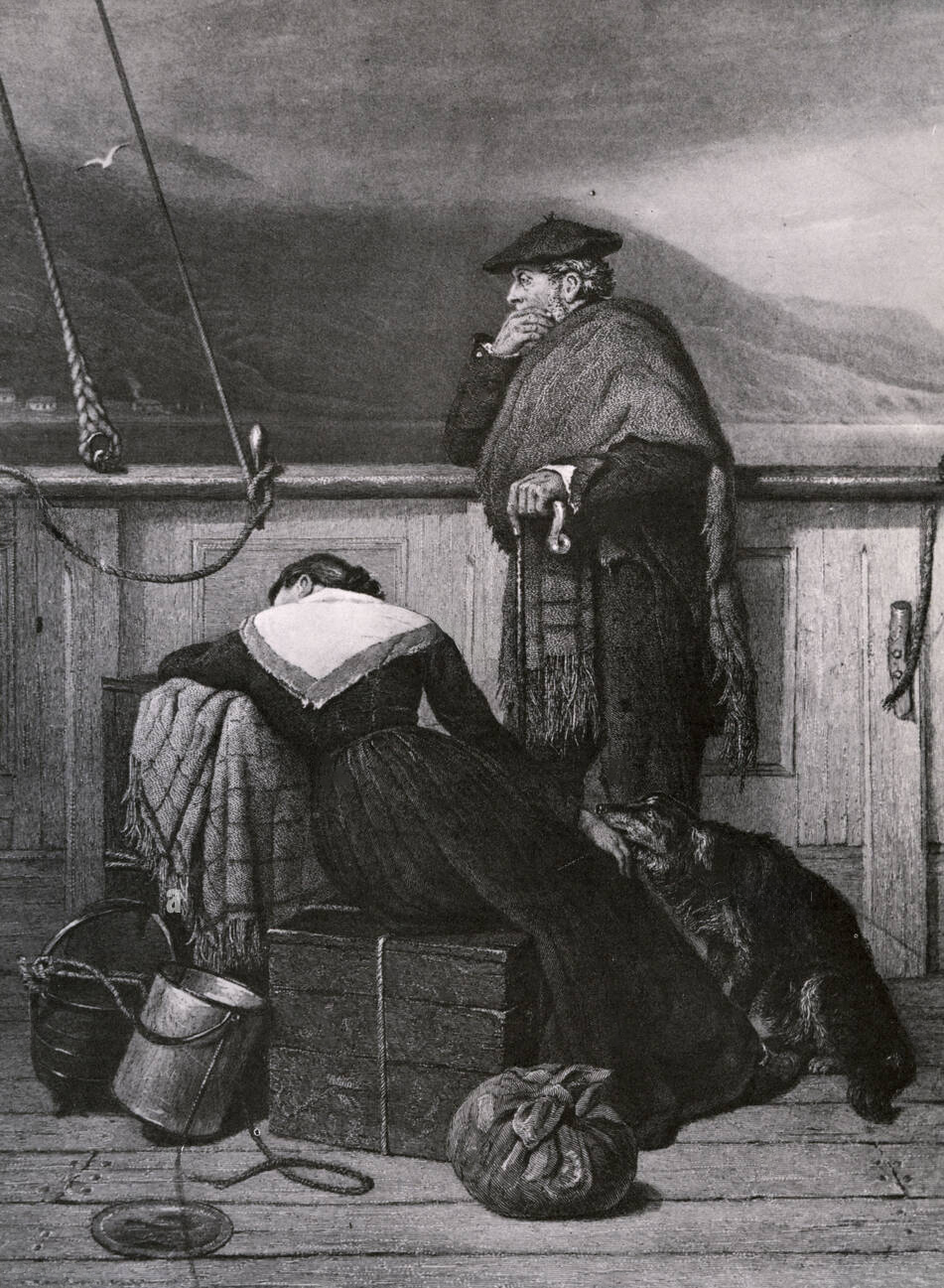

Donald MacLeod, who had immigrated to Canada before this, interviewed the ex-islanders and wrote, "Hear the sobbing, sighing and throbbing…see the confusion, hear the noise, the bitter weeping and bustle. Hear mothers and children asking fathers and husbands, where are we going? Hear the reply, Chan eil fios again - we know not."

What Are The Lessons Of The Highland Clearances in Scotland?

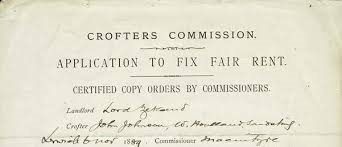

Rights and support for Highland tenants would not be achieved until the 1880s. Forced eviction was not legally eliminated until 1886 through the Crofters Holdings Act. Based on a model created in Ireland by The Land League this law gave tenants the rights to Fair rent, Free sale, and Fixity of tenure:

- Fair Rent - the courts, not the landlords, would decide what was fair.

- Free Sale of the Right of Occupancy - tenants could bypass the landlords and sell their interest in the land to another tenant.

- Fixity of Tenure - tenants could not be evicted if they paid their rents.

That is to say, only the courts could decide what constituted fair rent. Tenants could bypass the landlords and sell their interest in the land to another tenant. And tenants could not be evicted if they paid their rents.

It’s hard to arrive at exact numbers, but it is estimated that somewhere around 70,000 people were driven out of their homes and their country. At the start of the 18th century, roughly 30% of Scots lived in the Highlands and Islands. By the turn of the 20th century, the figure was only 8%. And there continue to be ripple effects down to the present day.

Not until 1976 did the government pass a law allowing the remaining Highland tenants to buy their lands – at highly-inflated prices. It was only in 1991 that the law evolved so that Highlanders were even allowed to plant trees again.

To this day, only a few dozen people own most of the Scottish Highlands. Many of the Islands belong to individuals or corporations. In 1993, two farm families on the Isle of Arran were evicted and their houses bulldozed – to make room for more deer.

There’s no real happy ending to this story. But there is an ironic twist. Many of the evictees of the Clearances immigrated to New Zealand. As it happened, they brought with them one very valuable item. Sheep. Today, odds are that if you wear any piece of tartan, a kilt, a shawl, or even a necktie…the mill who wove it for you got the wool from New Zealand. A tiny speck of poetic justice in a horribly tragic story.