Why The Scots Outlawed Christmas and How It Was Brought Back

It's time for Christmas. A time for crackers, and stockings, and delicious ham, and gifts for one and all. Oh you can just smell the roasting chestnuts in the air! But…did you know that Christmas as we know it now is only a very recent addition to the Scottish holiday calendar? It’s kind of the ultimate comeback story…I mean as holidays go. Here’s a look at where Christmas came from, why it disappeared for centuries…and how it came back.

Christmas in the Olden Times - From Paganism to Party

So how did we get this holiday in the first place? And to be clear, we’re talking about the celebratory aspects, the aesthetic of Christmas. Other channels, I’m sure, can do a much better job addressing the spiritual or religious meanings.

In the British Isles, many aspects of the holiday we now know as Christmas were adapted from ancient Scandinavian, Anglo-Saxon, and to a lesser degree Celtic and Roman customs roughly surrounding the winter solstice. These include burning the yule log, the giving of gifts, wearing silly hats, feasting, and partying long into the night…or nights.

In fact, the word Yule, or Jol, was originally the name for a whole lunar month in the Germanic and Norse calendar. That’s right, the Vikings essentially dedicated a whole month to celebration and relaxation. You find references to this in some of the Sagas, especially in the context of a protagonist “staying the winter” at the home of a friend or ally.

Many of the customs started by the old Germanic and Scandinavian tribes survived right on through the Renaissance all across Europe. For most of history, they lived side by side with Christian observances, sometimes being enhanced with Christian symbolism. For instance, the Twelve days of Christmas, the “Twelvetide”, was officially established as a sacred time for both worship and celebration by the Council of Tours in 567. However it’s pretty clear that this was putting a stamp of approval on an established period for wintertime festivals like the old Roman Saturnalia and Yule. And you guessed it, another name for Twelvetide was Yuletide.

Many of the old customs were just too popular to ignore. A lot of them revolved around sympathetic magic and good luck for the coming year. For example, if your family has ham for Christmas dinner, you can thank a Viking. The Germanic tribes used to hunt and eat a boar, which they considered a holy animal, at this time of year.

Another wonderful custom was wassailing. The name comes from the Old Norse ves heil and the Old English was hál and meaning “be in good health” or “be fortunate.” The Danish-speaking inhabitants of England developed this greeting into a toasting custom Was hail! With the reply drink hail!

This practice is so old that the Norman conquerors who arrived in the eleventh century considered the toast a distinctive native ritual. As a shared drinking ritual, wassailing bonded communities together and helped chase off the winter chill through the use of alcohol and tasty spices. It was an expression of hospitality which was of vital importance to fragile agricultural life.

The Yule log of course is another custom that stood the test of time. The burning log was meant to last through the entire time of the yule to represent the returning sun. For Christians, this became a symbol of a new age of light, inaugurated by Christ. These and a whole slew of other customs were enjoyed for hundreds upon hundreds of years. That is until the 16th century and the Protestant Reformation.

The Protestant Party Poopers Pounce!

In the process of questioning all the various institutions of the Catholic Church, protestants of many traditions also began to see sin and vice in the old holiday customs - whether they predated the Church or not (and honestly how would they have known the difference?). Basically they painted the Roman Church and folk culture with the same brush.

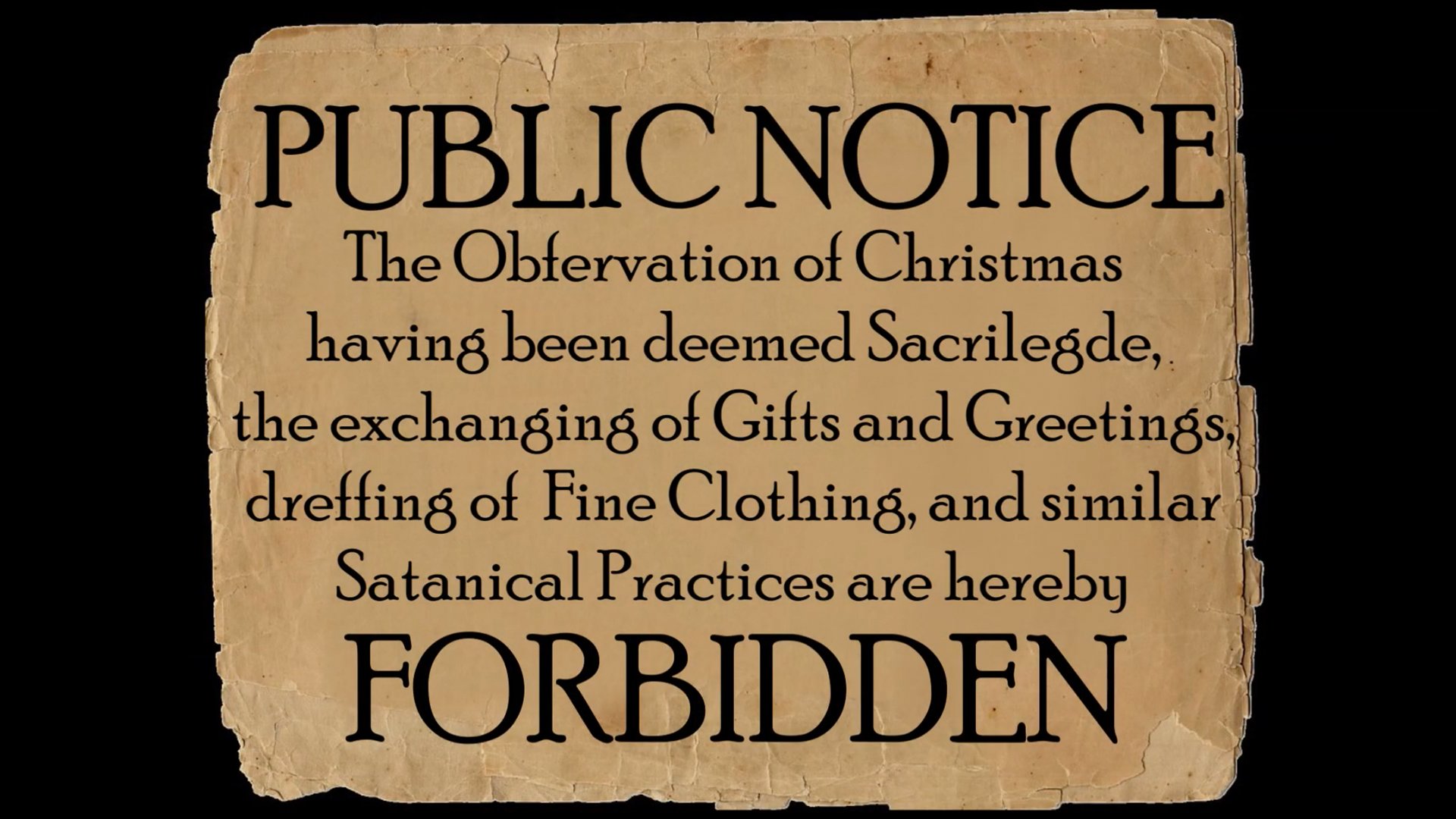

By the 17th century, several sects of Protestants actively discouraged any celebration of Christmas at all. Whereas your average folks went to mass and then partied the rest of the time, severe Protestants felt any form of social activity on this holiday was not supported by biblical writing and was therefore a sin.

John Knox was one such Protestant. However it was his later coreligionists, the Covenanters of the 17th century, who really put the kibosh on the party. Putting it very very simply, the Covenanters were the home-grown Scottish version of Puritanism. And in a law enacted in 1640, they brought the hammer down on Christmas.

"... the kirke within this kingdome is now purged of all superstitious observatione of dayes... thairfor the saidis estatis have dischairged and simply dischairges the foirsaid Yule vacance and all observation thairof in tymecomeing, and rescindis and annullis all acts, statutis and warrandis and ordinances whatsoevir granted at any tyme heirtofoir for keiping of the said Yule vacance, with all custome of observatione thairof, and findis and declaires the samene to be extinct, voyd and of no force nor effect in tymecomeing."

English translation: "... the kirk within this kingdom is now purged of all superstitious observation of days... therefore the said estates have discharged and simply discharge the foresaid Yule vacation and all observation thereof in time coming, and rescind and annul all acts, statutes and warrants and ordinances whatsoever granted at any time heretofore for keeping of the said Yule vacation, with all custom of observation thereof, and find and declare the same to be extinct, void and of no force nor effect in time coming."

The law was strictly enforced. People were hauled before the courts and kirk sessions for celebrating Christmas Day in almost any way. Bakers were even banned from making mincemeat pies. Shudder the thought!

The same sort of thing happened in England under Cromwell. Of course not everyone was in favor of the new law, but few dared say so publicly. Things got pretty bleak, and frankly boring. Then in 1660, the Stewart monarchy was restored and Merry ol’ England got back to being merry. But the Presbyterian Church, that is to say the Church of Scotland, never lost power in any real sense.

How strict was it? Pretty strict. The 18th-century Scottish antiquary, Robert Jamieson preserved the opinion of an English clergyman regarding the ongoing suppression of Christmas in Scotland.

"The ministers of Scotland, in contempt of the holy-day observed by England, cause their wives and servants to spin in open sight of the people upon Yule day, and their affectionate auditors constrain their servants to yoke their plough on Yule day, in contempt of Christ's nativity. Which our Lord has not left unpunished, for their oxen ran wud, and brak their necks and lamed some ploughmen, which is notoriously known in some parts of Scotland."

I can’t speak to the divine curses, but this just oozes with contempt on the part of the minister. And yeah, these proscriptions were extremely serious. You had to work. Period. The bit about women spinning yarn is especially telling. Since the very beginning, there existed a Chrtsmastime taboo against it. Women normally filled every moment they could with spinning thread for weaving. But not during the yuletide. They were, shockingly, expected to lay aside their regular work and relax. Having a full spindle to show off at the start of the holiday was considered good luck as well as a reminder to the household “Yo. I’m on vacation too, fam.”

So for the next 300 years Scots simply went to work on Christmas Day as though it were any other day of the year. Mind you, I doubt people were very productive. But what is a stir-crazy Scottish party animal to do with no Christmas?

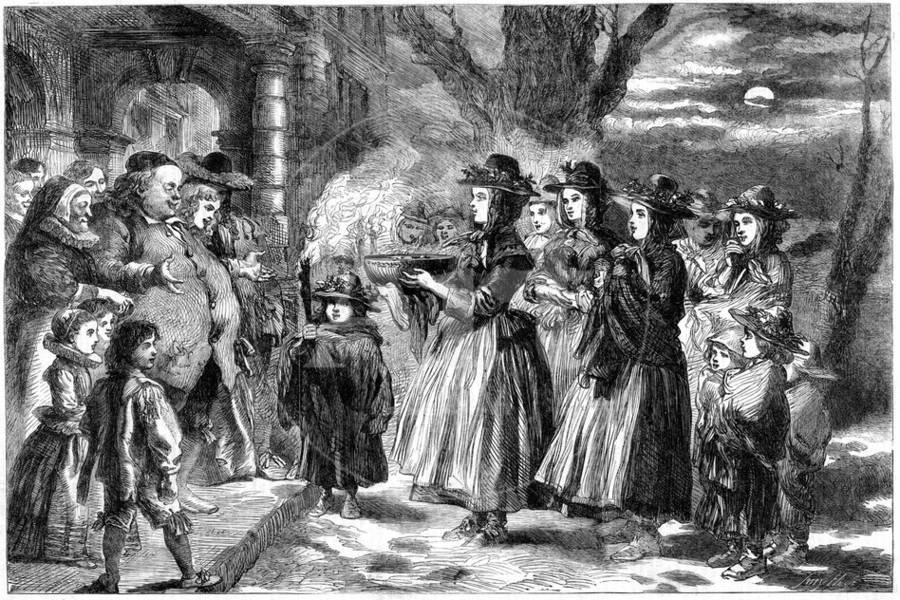

Well simple, move the party to another date! Specifically January First, called Ne-erday. And more importantly New Year’s Eve aka Hogmanay. Since this was an entirely secular feast, the Church could do nothing about it. Evidence suggests the Kirk tolerated Hogmanay – as long as it didn’t lead to dancing.

A few of the old folk customs from pre-Puritan days thus survived. For instance various practices designed to bring good luck in the new year such as first footing and redding the house. First footing is where a tall dark man with gifts of coal, shortbread, salt, black bun and whisky enters your home bringing good fortune with him. Redding is a winter version of spring cleaning. Sort sweeping out the old luck and preparing for the new. And naturally, everybody set things on fire.

Several days were dedicated to the celebrations, and this was a direct inheritance from the Yuletide. In Scotland they came to called The Daft Days - the crazy days. It was a revival and preservation of the idea of a topsy-turvy “rules are on hold” mindset that goes all the way back to the Roman Saturnalia. That’s where the silly hats come from, by the way. The Daft Days lasted from December 25th through New Years, and into the first Monday of the year, known as Handsel Monday which was marked by the exchange of small gifts as good luck tokens. The word handsel derives from Old Norse and Anglo-Saxon and means “to give into the hand”. So there you go.

So Scotland found a way to party on. But then…what changed to bring back Christmas itself?

Well, in one word, Hitler.

Santa Claus Arrives from the Good Ol' USA

Seriously here’s the deal. By the 1930s, radio was making the world much smaller. Even people in rural areas of Scotland could listen to holiday broadcasts by the BBC. Then along comes world war II. All kinds of sentimental programming is being produced to help boost morale. Plus, now you’ve got the Yanks in your backyard. American troops were stationed all over the UK and especially in rural areas. And naturally they were enjoying their own Christmases. After the war, exposure to how the rest of the western world celebrated secular christmas just kept on increasing and increasing. And FOMO really took root.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, big sassy pantomimes appeared in theatres across the nation, even though rationing was still a grim reality. In case you don’t know Pantomimes, or Pantos are these adorably tacky vaudeville-type stage shows put on during the Chrsitmans season. They’re supposed to be for the kiddies, but let’s be real…everybody loves them. Radio, and then television, broadcast these as well as other holiday programming.And yes, commercialism was a factor.

At first there was a pretty strong class divide. As wartime privations dissipated, the Middle Classes, who had easier access to media and more spending money, adopted the English Dickensian Christmas. Blue collar people meanwhile tended to save their money and energy for Hogmanay. But it was just a matter of time. In 1958, the Scottish Parliament finally gave in.

Scottish Christmas is a Holiday with Ancient Roots and Modern Energy

Today Scotland embraces most of the modern Christmas customs such as hanging stockings for Father Christmas, Christmas pop music and of course faery lights everywhere. Seems they also especially enjoy German-style Christmas markets. So yes, commercialism is a big part of the story. All of this history means that Scotland has perhaps the richest winter holiday season of any nation in the world. And that is truly special.

Bottom line…..winter makes people think about the fragility of life. That makes people want to embrace life. And that leads to parties. Since ancient times we have always felt a need for hope in the darkness. And as social animals we crave joy and togetherness. Is Christmas commercialized? Yes. Heck I even think the Puritans had a point when it comes to excess that leads to self harm. But…it’s a VERY small point. I think we can be both spiritually-minded and fully engaged with the lighter side of life. If we’re smart, we keep that balance all year round. But the winter festivities are pretty ideal for pushing us to seize the day.

So whatever traditions you choose to incorporate into your celebration, make Christmas your own. Make it fun, and beautiful and memorable. You’ll be following in the footsteps of countless generations.