The Clans of The Scottish Highlands and the Tartan Craze of the 19th century

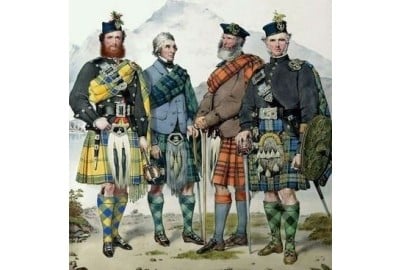

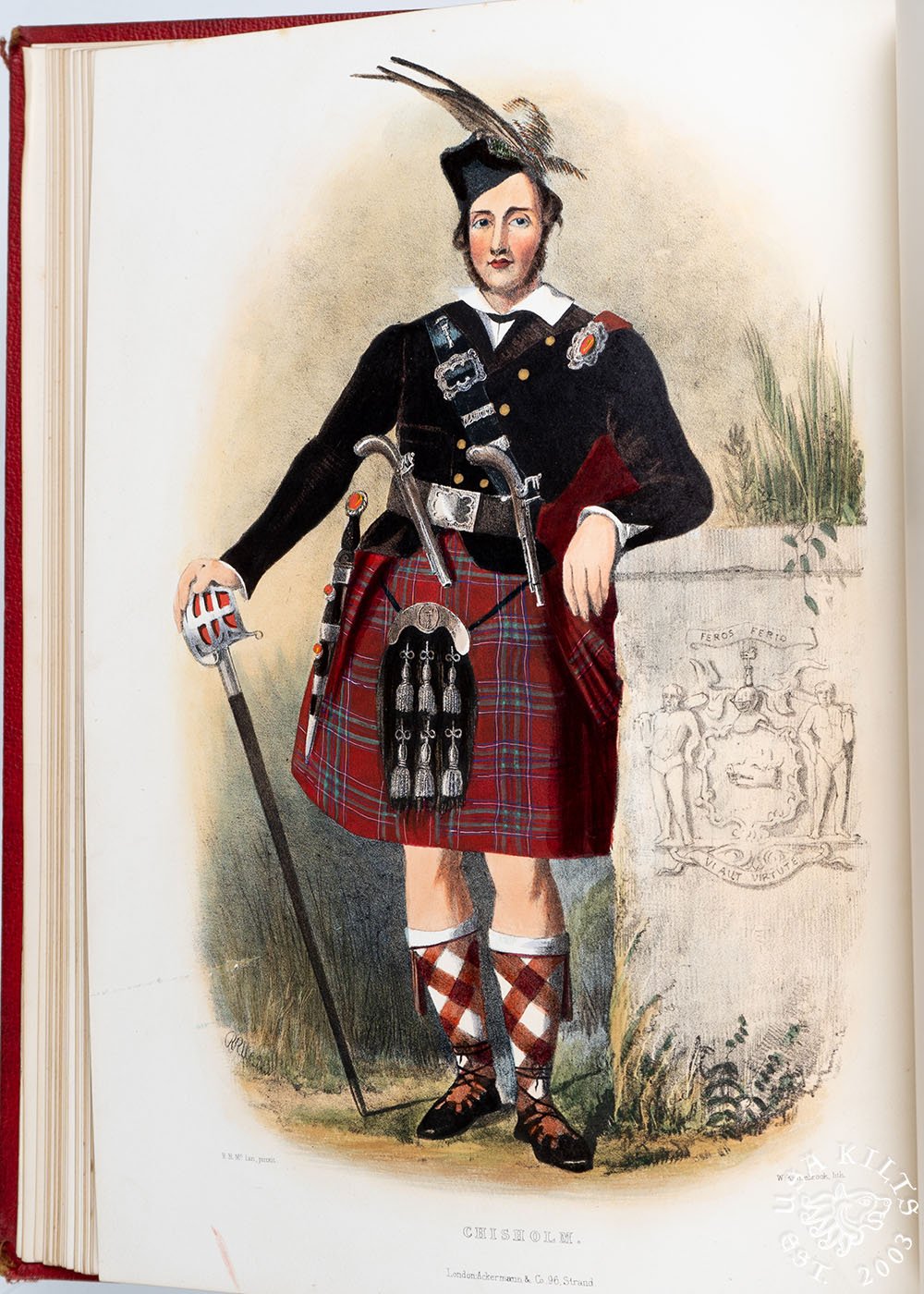

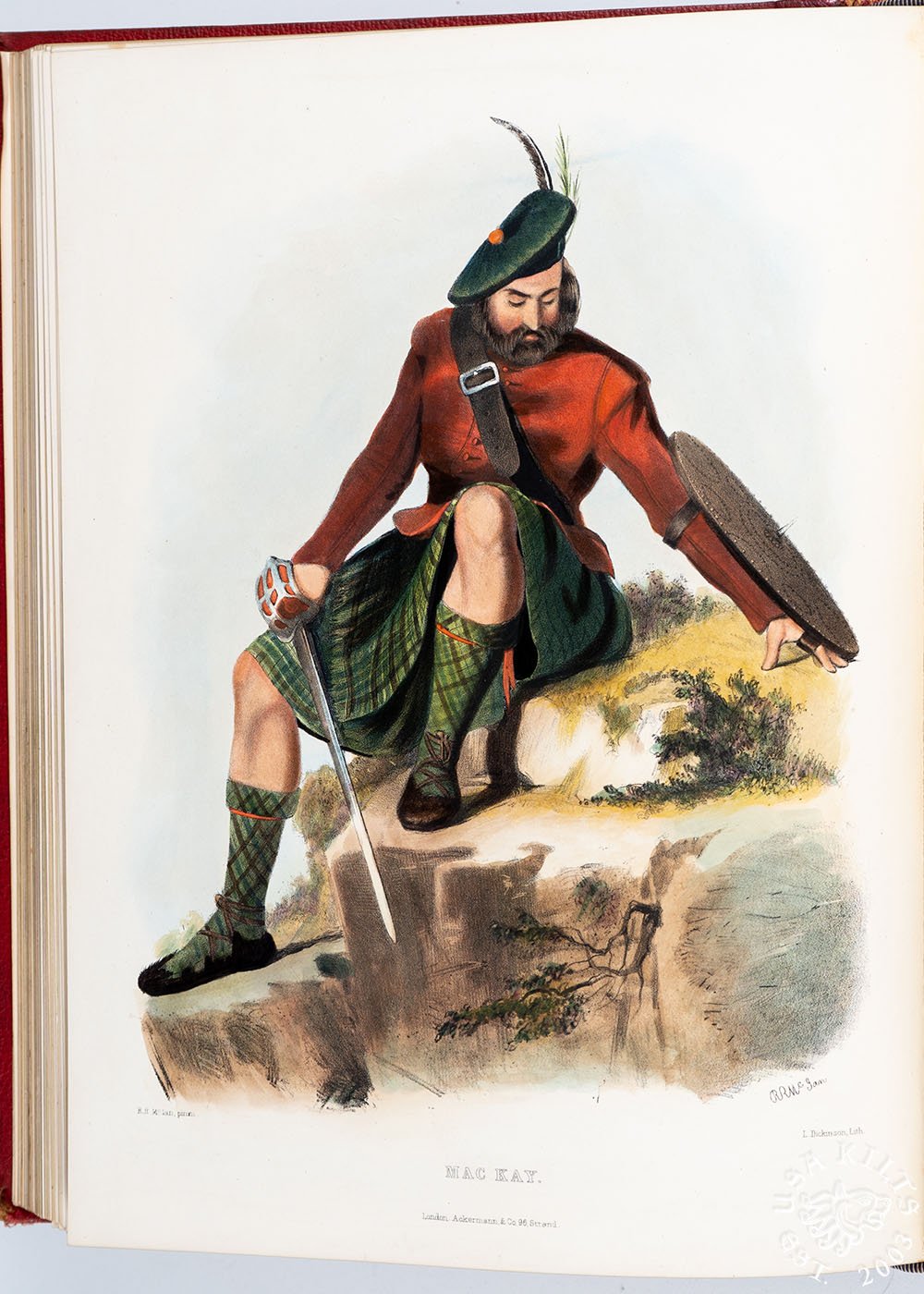

The Clans of The Scottish Highlands by James Logan and R R McIan is one of the most famous depictions of Highland Dress in history. You’ve probably seen images from these books all over the internet. And you may own a reproduction of one of the richly-colored illustrations. Actually, you may even own, or have seen in an antique shop, pages of this book cut out and mounted as wall art.

There are only a few surviving specimens of the original printing from 1845.

It is simply a gorgeous book. But what else is there to say about it?

Essentially this. The Clans of The Scottish Highlands represents the Tartan Craze of the 19th century. Don’t fool yourself into thinking the Highland Dress and kilt culture is an unbroken line going back to ancient times. The truth is that without the passion and concerted efforts of certain elites, including Queen Victorian herself, we might not have such a rich national dress and cultural artform to enjoy today.

What were the Acts of Proscription and did they work?

For context, we have to go back 100 years before this book was created. Tartan hasn’t always been as popular as it is now. Following the Jacobite Rebellions of the 18th century, anti-Scottish sentiment swept across England. After the defeat of Charles Edward Stewart (the “bonnie Prince”), Parliament feared another bloody rebellion was just a matter of time. So they took action to limit the influence of various groups across Scotland - especially the Highland clans. The display of rallying symbols of Jacobitism were outlawed.

The most famous of the so-called Proscriptions was the Dress Act of 1746. This law forbade the wearing of complete traditional highland wear across Scotland. Essentially a tartan suit was seen as a defacto military uniform due to the recent conflict. As such it could be considered a rallying symbol; a piece of Jacobite propaganda.

The overarching goal was to weaken Scottish cultural identity which of course had been more of a Highland thing. These measures lasted for about 40 years. They were difficult to enforce in rural areas, but they did have an effect. Traditional highland wear (including the kilt) fell out of fashion with those of means. But the more rural the area was, the more likely it was that something was retained, often out of sheer practicality as clothing was expensive. People kept on wearing elements of highland dress; a kilt here, a shawl there, etc. Thus tartan never truly died. It was just waiting for a chance to really bloom again.

How did Romanticism make the Scottish Highlands popular?

Now, there is nothing more evil than an enemy you are afraid of. Conversely there is nothing more romantic than an enemy whom you have defeated….especially if you feel a little guilty about winning. It’s a pattern you see throughout history from ancient Rome to the American West.

In the young but rapidly expanding empire of Great Britain this pattern applied to the Scots. By the late 1700s, the Empire needed troops and working men more than ever. Meanwhile greater affluence led to a more or less new invention: tourism. (yes, Scotland has been a tourist destination for over 250 years - sympathies to anyone who finds living in a tourist town annoying)

The new middle class and smart nobility developed a fascination with Scotland…the landscape they could now explore on holiday, the old “quaint” customs, the tragic romance of a “primitive” warrior people. And of course tartan.

All this was part of an international zeitgeist we know as Romanticism. It was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that rejected the stiff rationalism of the Enlightenment. Fueled by nostalgia, medieval history, and nature, Romanticism emphasized individualistic, nationalistic and emotional responses to life. Think Rousseau, Lord Byron, Beethoven, and much later on, John Ruskin.

How did Sir Walter Scott create Scottish identity?

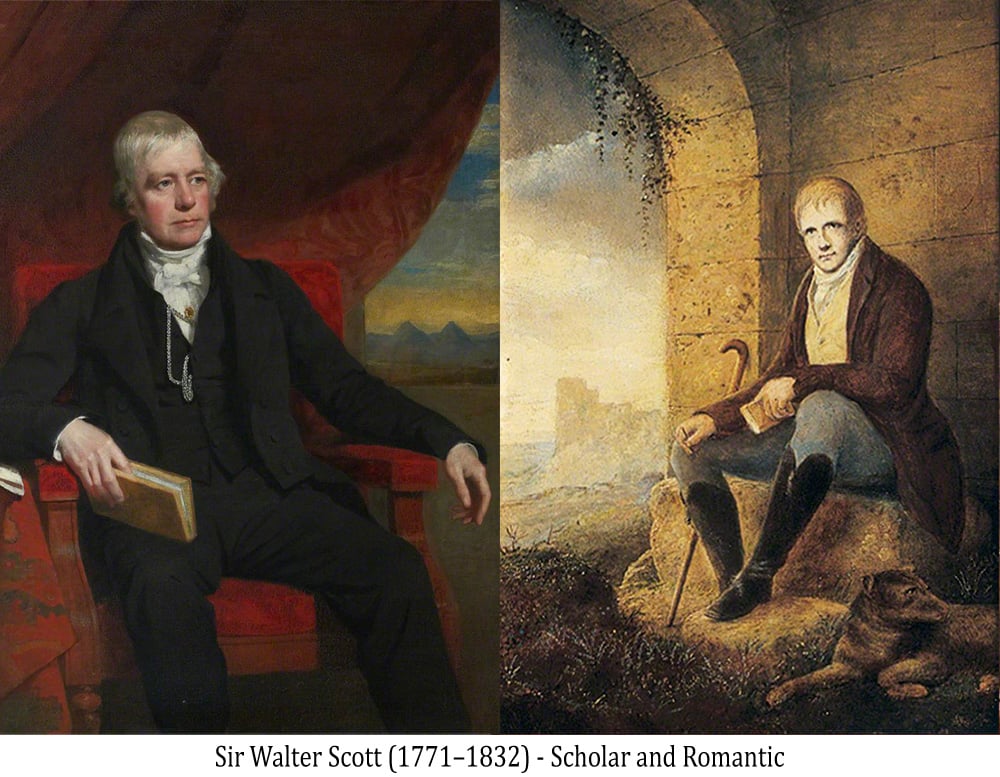

And that background brings us to Sir Walter Scott. Born in 1771, Scott was an avid lover of Scottish History and Culture and a true Romantic. Despite being formally trained as a lawyer, his real passion was writing and he would go on to pen a series of novels and epic poems that brought a powerful romantic view of Scottish history to life.

Scott became an international sensation. He was even offered the position of British Poet Laureate at one point, though he declined.

Now, Scott was not just in this for the fantasy or for profit. He was part of an intelligentsia that truly desired Scotland’s return to greatness. And to accomplish that, these men needed to establish a national identity; one rooted in the past but also energized by the current day. Scott was a leader and the chief propagandist of this movement.

Scott’s crowning achievement was formally “reintroducing” Scotland to the rest of Britain through a royal visit. In 1822, he was able to use his popularity to convince King George IV to visit Scotland. This was momentous; the first time in nearly 170 years that any British Monarch had traveled to Scotland.

How did King George IV’s visit to Edinburgh affect Scotland?

The visit was political theater like never before seen. Ostensibly, the visit was intended to boost the popularity of the deeply unpopular King in a region where relations had been deteriorating for decades. In reality, the visit was part of a plan by Parliament to distract the King while they handled post-Napoleonic negotiations at the Congress of Verona.

Walter Scott (now SIR Walter Scott, Baron of Abbotsford) managed much of the pomp and circumstance for the event, often giving advice to the king and planning key parts of the ceremonies and festivities himself. One result was that he convinced King George to wear proper Highland Dress during his visit. Or as Scott put it “the Garb of Old Gaul.”

The cost of George’s outfit was exorbitant, but he did cut a pretty fine figure. This despite his girth and the fleshtone stockings he wore so as not to reveal his actual legs. Neither of these details made it into the official portrait.

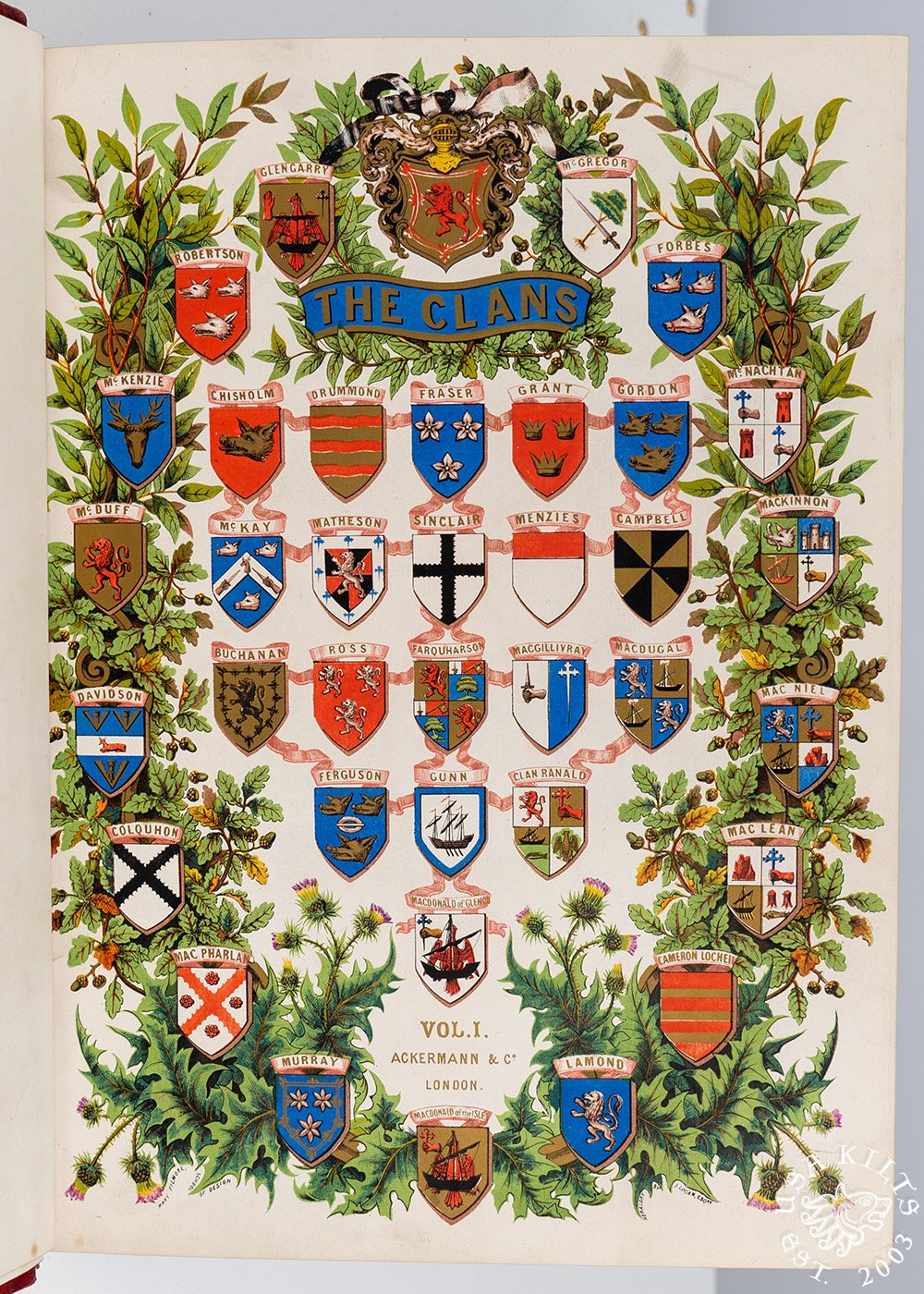

Of course, if the King was wearing a tartan kilt it would not do for any Scottish elite to attend in anything but. Suddenly, everyone needed Highland dress. And every clan chief needed a tartan, whether his family had ever used a designated one or not. Mills were swamped with orders, chief among them the great W. Wilson & Son Bannockburn. The number of “official” clan tartans was about to explode. The so-called tartan craze had begun.

Was the Tartan Craze global?

The king’s visit was a massive success and turned interest in Scottish culture into a veritable bonfire. Now that it was safe, acceptable and fashionable, tartan and Scottish culture became symbols of pride for the British Empire as a whole.

Few people were more enthralled with it all than a certain young lady from London named Victoria. Born at Kensington Palace on May 24 1819, Vicky came of age with the tartan craze.

By the time she came to the throne as Queen, she was already deeply fascinated with all things Scottish. Her interest is well documented in her writings, her wardrobe, her purchase of the Balmoral estate, her ordering of the restoration of Rosslyn Chapel, etc etc etc.

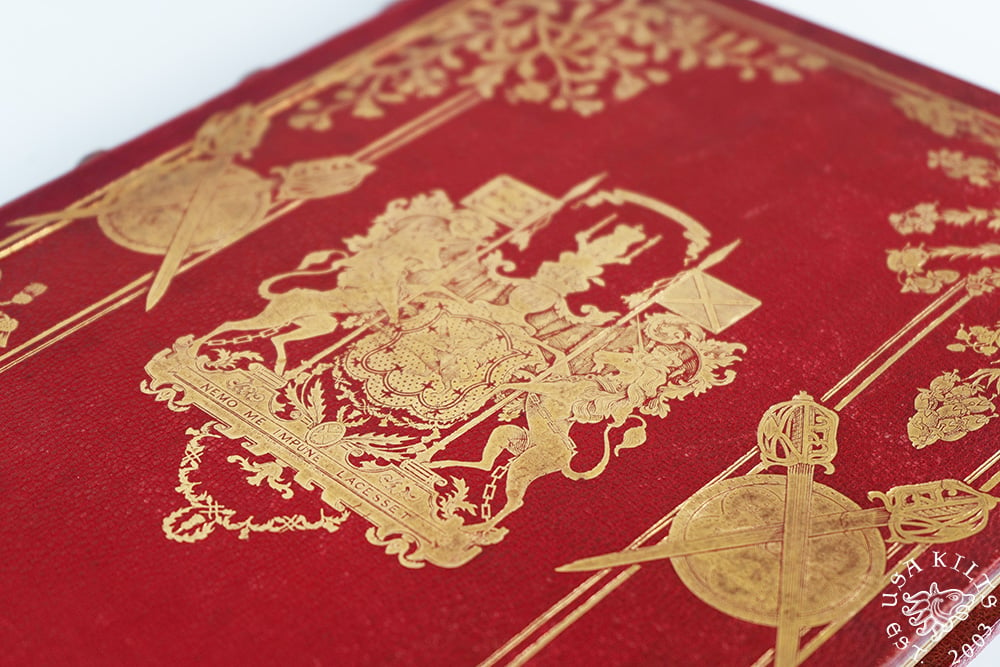

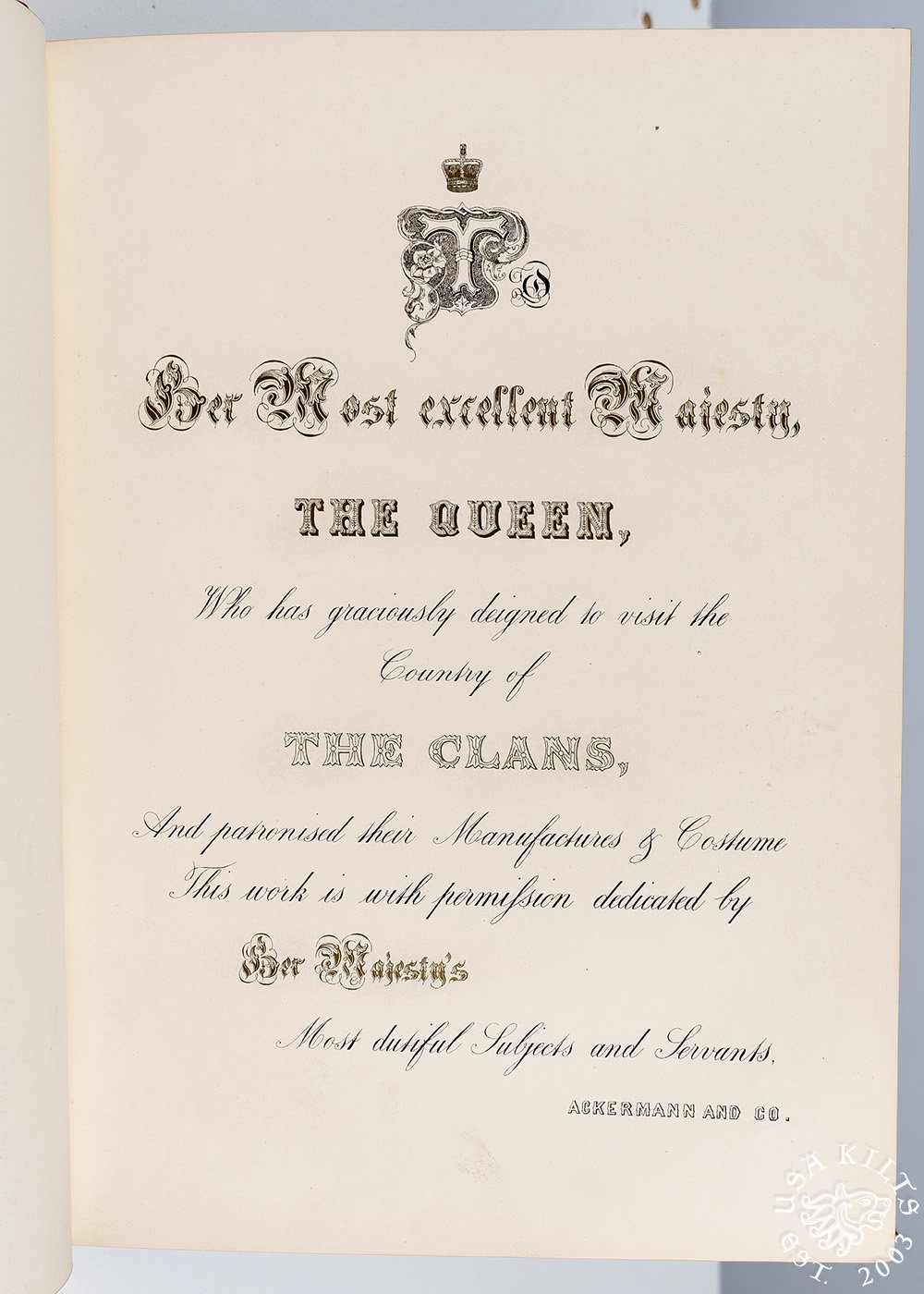

We have Queen Victoria to thank for The Clans of The Scottish Highlands. Her Majesty wanted to do her part to honor and preserve tartan and Highland culture so she commissioned the creation of a definitive work.

Who painted the Victorian images of Scottish Clan Tartans?

Two individuals won the commission for The Clans; Author James Logan and illustrator R R McIan.

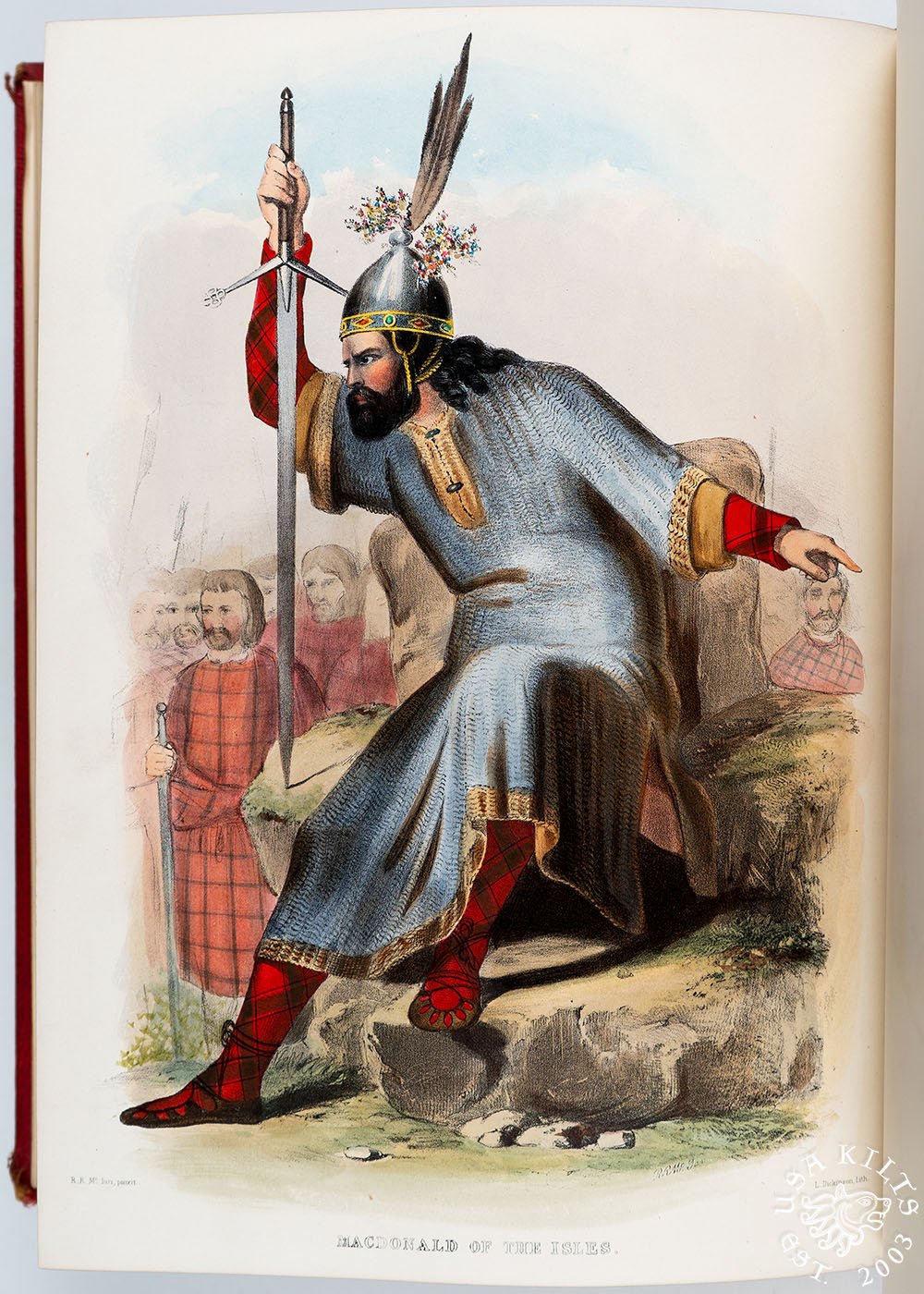

Robert McIan was born in 1803 just outside Inverness. Unfortunately, that’s really all we know about his early years. McIan’s life becomes a bit more defined in 1825 when he began touring across Britain with an acting troupe performing in a dramatization of the life of Rob Roy. He was about to find a bit of an acting niche, portraying the “tough highlander” character in various productions.

However, McIan had another passion; painting. He moved to London, continued acting to pay the bills, and developed his skills as a painter. In 1830, McIan would join the ‘Gaelic Society of London’. This group was committed to preserving the Gaelic language and culture in Scotland and would serve as a major influence on McIan’s art. He would use this inspiration to create illustrations of mostly medieval Scotland. The popularity of these fanciful images lodged McIan firmly in London’s art scene. Sadly, Robert died in 1854, not longer after the creation of The Clans of the Scottish Highlands. We can only imagine what he could have achieved had he lived.

The author of The Clans, James Logan, was born to a wealthy merchant family in Aberdeen sometime around 1797. He was formally educated and studied to become a lawyer. However after suffering a head injury while playing sports, he was forced to withdraw from school. Logan bounced around a number of careers before he found success as a writer. His first major work was a collection of stories and illustrations; scenes Logan encountered while on a series of walking tours across rural Scotland. His book, The Scottish Gael - or Celtic Manners as preserved among the Highlanders, was so popular that he was invited to present a copy to King William IV (Queen Victoria’s predecessor). Logan spent much of his life documenting Scottish culture as he saw it and his work has had a large influence on how we see Scottish culture today.

So what actually is in The Clans of The Scottish Highlands?

As you undoubtedly realize, this massive tome is a catalog of detailed descriptions of traditional Highland dress. The Clans is widely considered to be one of the first comprehensive, illustrated records of Highland dress in the world if not the first. The introduction itself makes that boast and purports that the work is highly accurate; free from the errors of previous romanticized documents.

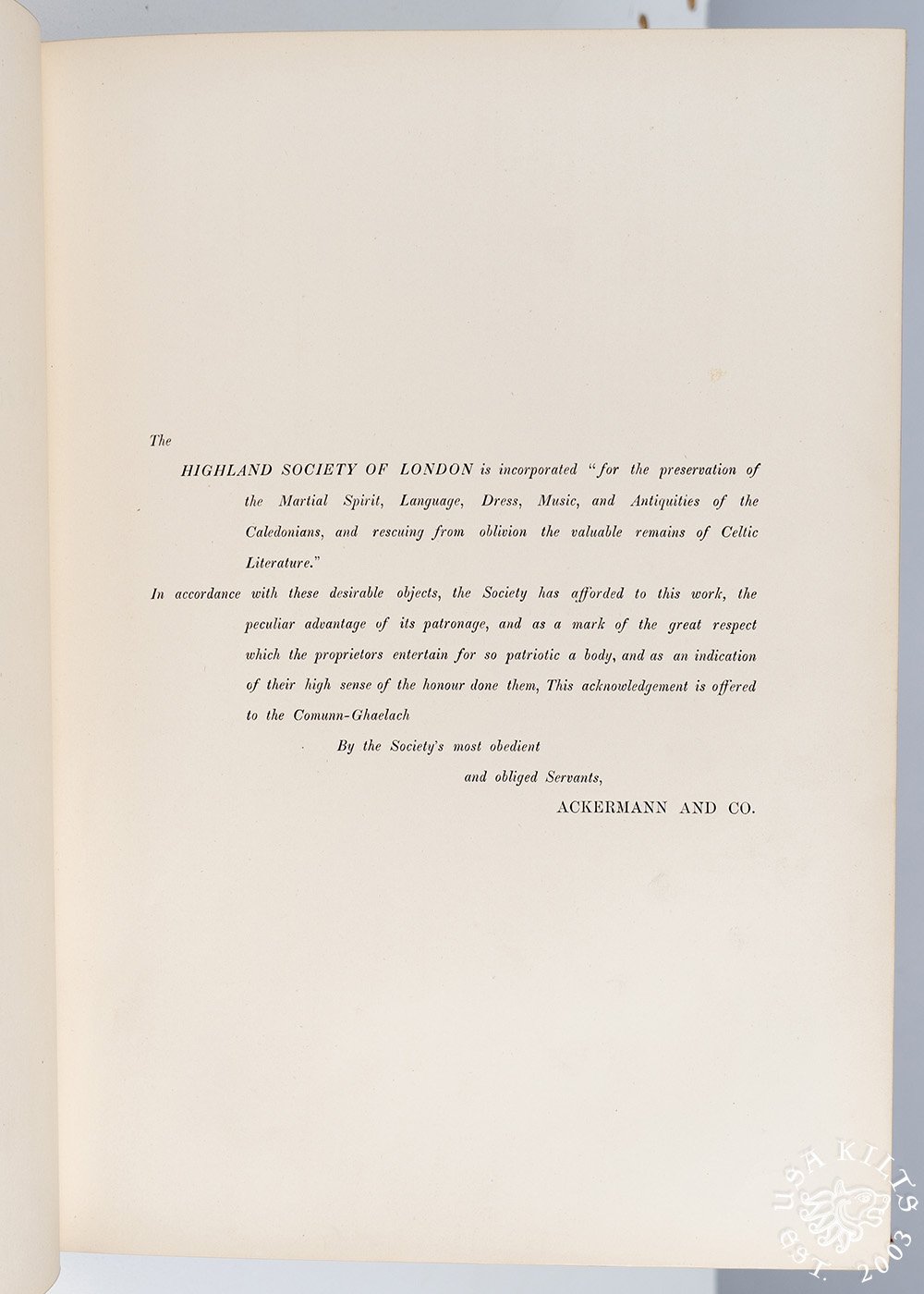

Logan and McIan were under a lot of pressure to make it so. The list of subscribers to the project (the financial backers) included Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, the King of France, various other European nobles, the Royal Academy, the Royal Library of Bavaria, and perhaps most critically, the Highland Society of London, who have their own full page acknowledgement in Volume One - right after the Queen’s.

The general sense is that McIan,Logan and their publisher Ackermann and Co. knocked it out of the park. From clan chiefs in tartan revival suits to warriors in great kilts and just about everything in between, The Clans showcased as many forms of Highland Dress as it could. And interwoven with each illustration were exciting histories or legends related to each of the 73 clans represented. All in two very heavy 22- by 15-inch volumes.

In 1845, the collection was presented and dedicated to Queen Victoria at the centennial commemoration of the last Jacobite Rising. Those original tomes are still maintained by the Royal Collection Trust. The printer, Cook and Company, put the work into mass production soon after and by 1847 it was in homes across Britain.

Is The Clans of The Scottish Highlands accurate?

As we said, the document purported to be an accurate chronicle - official information on the major Scottish clans including their tartans, histories and noted leaders. Logan interviewed dozens of Clan chiefs and others to gather his facts.

However with hindsight we know that some of the research and interpretations were, well, romantic. Logan and McIan did a fine job worthy of their royal patron, but they were people of their time with the resources available to them then, as well as the cultural filters of their society.

The Victorians were often tempted to color facts to make them conform to their own ideals. So can we trust the information in these books? Well, let’s just say “trust but verify”.

It is safe to say that images in the collection that show contemporary Highland Dress of the early to mid-19th century cane be trusted. Conversely, images set in a historical seting such as the Jacobite Uprising of 1745 or the Middle Ages can not be taken at face value. "Artistic License" rules the day here.

The work of separating fact from myth has occupied Scottish historians for decades and the best advise is to seek out recent works by acknowledged historians if you want to verified accounts of clan history. All that said, The Clans of The Scottish Highlands is a critical document.

The next major work of any similar focus would not come until 1870 when Kenneth Macleay’s watercolors of Queen Victoria’s staff at Balmoral was published. And of course while that collection is beautiful and an accurate presentation of Victorian fashion, its scope is miniscule by comparison to The Clans.

How Do Scots See Tartan Today?

As for the tartan craze, it is safe to say it has had its ups and downs. ‘Tartan tat’ and ‘shortbread tin’ characterizations of Scottish culture and history have fostered cynicism among many Scots regarding tartan and the traditions handed down to us from the 19th century. Some even reject it all out of hand as “invented tradition” which was imposed on the country by outsiders.

There is some truth to this. However, if some of our modes were invented, it was done so by Scots as much as, if not more so, than by the English. And it was done with the best of intentions. Like it or not, the romantic notions about Scotland’s past, her arts, and her national character are here to stay. Rather, it is upon the current generations to decide what to build on; to reject what seems shallow, tawdry or simply false and embrace the good and the unique as a worthwhile legacy.

And I for one think that is what is happening. The Scottish Register of Tartans, the official body of the Scottish government charged with recording any and all tartans ever designed (and a branch of the Court of the Lord Lyon , Scotland’s Royal Heralds) receives something like 300 new submissions every year.

In 2024, the V&A Museum at Dundee, a branch of the Victoria and Albert Museum, held an exhibition on the history, evolution and current artistic expressions of tartan. The exhibit received resounding praise. One wonderful side effect of the project was the uncovering and introduction to the public of the oldest fragment of true Scottish tartan ever discovered - the Glen Affric tartan.

I mention these two facts to underscore my point. The love of tartan and Highland dress is going strong and getting stronger. The hard work of preserving, and creating, Highland Dress may have been somewhat artificial at the time. We may not have the sense of desperation that Sir Walter Scott felt, but we owe all of the old ‘true believers’ an immeasurable debt. Yes, even Ol’ Queen Vic.

If you ever have the chance I highly recommend perusing and reading The Clans. If you want to learn more about the history of tartan in the 19th century, I recommend the work of Dr. Rosie Wayne at the Scottish National Museum. The most popular general history of Scotland right now is Scotland, The Story of a Nation by Magnus Magnusson.